[ad_1]

“Yaya, you know you could be a coach,” a manager once told me. “What?” I replied. I was confused. I’d never considered coaching before. “I just want to play,” I said. At the time, I was sure of it. I wanted to finish my playing career properly. But those words sparked something in me, when it had never previously crossed my mind. I wasn’t ready at the time because I wanted to carry on playing, but also because I knew then – and know now – that I couldn’t have coached at that age. I was so shocked! I still had so much to learn.

At Manchester City, Pep Guardiola and I used to talk after training about specific things, parts of the game that he loved to analyse. He saw that I understood the game. Sometimes I would also speak with the chairman, Khaldoon Al Mubarak, too. He agreed I should consider becoming a coach. Up until then, I just thought I was thinking about how I was playing in a deeper way. I didn’t really realise I was thinking like a coach. I’d always thought in that way. It came naturally to me.

In the Manchester City teams I played in that won titles, out on the pitch, we were always looking for ways to improve; ways to get the most out of each other. David Silva and I would talk constantly. Samir Nasri, too. If we weren’t finding a route to Sergio Agüero, we’d make the decision to change things. “This isn’t working,” I’d say. “Let’s swap positions and see how that works.”

Of course, I had great managers at City – Roberto Mancini, Manuel Pellegrini and Guardiola. They would give the team a platform and structure, but communication between players is so important. You need communication on the pitch. We found we made each other better because we understood what we were doing so well.

It was the same with my midfield partners, whether it was Javi García, Gareth Barry or Fernandinho. We knew we had to help make each other’s jobs easier by having balance in midfield. I was always the more attacking one, and I knew I could make my midfield partner better by not losing the ball easily, just like he could make me better by winning the ball back as quickly as possible after we lost it. I helped the defensive midfielder by slowing opposition play down when I could, and stopping passes into midfield, and he made me better by anticipating any passes that made it past me.

Later, when Kevin De Bruyne joined City, we just tried to make him happy. “How do you want the ball?” I asked him. “Do you want to receive passes in the middle or do you prefer to be out wide?” He gave me information and I used this information to help make him better.

I wouldn’t say I was demanding as a player. I just saw the potential in my teammates and wanted them to be as comfortable as possible. That was something I learned at Barcelona: everyone is different. If you don’t talk with them and it’s only the manager giving information, you can’t make your teammate the best they can be. If they score a goal, it is a goal for all of you, so why not help them whenever you can?

My understanding of the game comes from my footballing education back in Ivory Coast. As a child I had grown up just playing football with my friends in the street just for enjoyment. We put the ball in the middle of the pitch and played. Pass, pass, pass, score a goal, finished.

But then a coach called Jean-Marc Guillou came to watch us, and he took me and the other most talented players to the ASEC Mimosas Academy when I was 13. He helped us learn the difference between amateur and professional football and develop a better understanding of what we were doing. He gave us the chance to realise our dream.

Jean-Marc worked us really hard. We trained three times a day, sometimes six days a week. We’d start at 5am, go to school, go back to training, go back to school, and then train again at 4pm. Day after day. I learned why commitment and hard work are so important. I made a lot of sacrifices at a young age.

I asked loads of questions. I wanted to know what to do and why we should do it. Sometimes I would sit with Jean-Marc for an hour after training, talking about what we had done. He didn’t focus on specific positions with us. That meant that the way we were developed was unique. We learned to be able to fill in for a teammate who was injured or having a bad game. If we needed a right-back, anyone could do it.

Jean-Marc knew we would have to learn to play a particular position eventually, but we were all brought up to be versatile footballers. He gave us the belief we could play anywhere. We didn’t focus on the characteristics of certain positions or roles; he just wanted us to develop us as players.

When you look at who Jean-Marc has brought through – players such as Emmanuel Eboué, Didier Zokora, Salomon Kalou, my brother Kolo and Gervinho – you can see how versatile his players were as professionals. He was amazing like that. Growing up, Kolo was a striker. He started out at Arsenal as a right midfielder, before moving to central midfield, then to right-back, and he eventually settled in central defence, where he had a great career.

When I earned a move to Europe at the age of 17, to Belgian side Beveren, I didn’t even know my best position. To be honest, at first, I was scared. I was very skinny – almost small. Everyone else looked massive! It was amazing that I had made it to Europe. To go from the streets of Abidjan to playing European football was unbelievable. Not many people manage that.

But when I arrived, I didn’t know what position to play and the size of the players scared me. There were four of us from Ivory Coast and we didn’t know if we could compete against these men. But when we got on the pitch, we relaxed. We were more used to the ball, we could play out from the back, we could receive the ball under pressure – and because we understood what was being asked of us and had played in lots of different positions – we became leaders on the pitch. We used our brains more than the players who were already there and that helped a lot.

It was the same when I came to England. Everyone told me about how strong, tall and physical the players were, but my experience in Belgium helped me. It was difficult to begin with, but I got used to English football quickly.

It was only at City that I discovered my best position. I’d played all over previously, including at centre-back for Barcelona when we won the Champions League final in 2009. But at City, playing as a box-to-box midfielder or as a No 10, I found the positions where I was best.

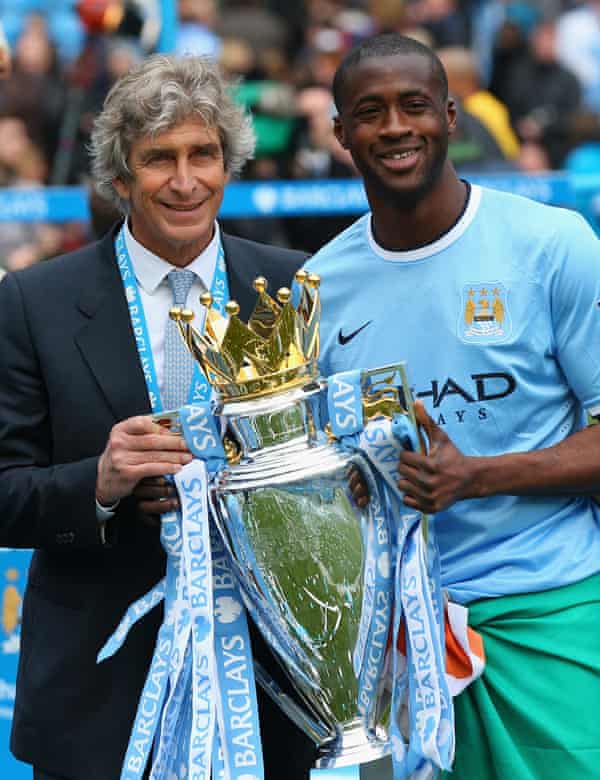

I had the most responsibility under Manuel Pellegrini. When he came in, he told me straight away that he saw me as a leader. “Vincent Kompany is the captain,” he said. “But when Vincent is not there, you will be captain.” I told him I was not ready for that. “I see how you talk with your teammates,” he said. “Even at the dinner table, you talk about football.”

He saw his central midfielders as the most important players on the pitch and told me to go wherever I wanted to influence the game, because Fernandinho would cover for me. He pushed me, gave me more responsibility. He said he didn’t want too many passes – he wanted us to run with the ball and attack the goal. Vincent missed a few games in that 2013-14 season, so I captained the team quite a bit. I scored 20 goals in the league alone and we won both the Premier League and the League Cup. I really enjoyed that extra responsibility.

The coaches I had across my career helped get the best out of me. Jean-Marc saw my talent, put me in an academy and now – after winning four African Player of the Year awards – I’m one of the best players Africa has ever seen. Roberto Mancini showed belief in me that I could play in central midfield, and be a leader, for Manchester City. Without them, I wouldn’t have achieved what I have.

Helping players develop like they did with me is what inspires me to be a coach. The best coaches are the ones who can do that. Look at Jürgen Klopp – he is a genius! He has taken so many players to the peak of their game: Sadio Mané, Mo Salah, Jordan Henderson, Georginio Wijnaldum, Fabinho, Virgil van Dijk, Andy Robertson. They came to Liverpool as good players, but now they are all great. Then there are loads from the academy, too.

I have to be honest, though; it is difficult to completely give up on football. Maybe my legs have one more year left in them! But I have started to realise how good it is to be a coach. The coronavirus pandemic has made things difficult in a lot of ways – it was the reason I left Qingdao Huanghai in China in early 2020 – but it has given me the opportunity to learn. I have started doing my coaching badges and think about the next chapter.

I’ve already made good progress in gaining my qualifications, but sitting in an office the whole time – that’s not me. I want to be out on the grass, interacting with other people, exchanging ideas. I’ve been very lucky that Chris Ramsey has given me the opportunity to do that at QPR. I’ve been able to lead coaching sessions with the younger age groups, watch Chris coach and learn from him, as well as lots of other good coaches like Andrew Impey and Paul Hall. Les Ferdinand has been great, giving me the chance to watch these coaches in action. They have pushed me to learn. I’ve also had the chance to go to Blackburn thanks to Stuart Jones and the PFA – through Geoff Lomax – have given me great opportunities too. I’m learning all the time, and I love it!

At QPR, after the sessions, I spend time chatting with the players. It is amazing to see how committed they are. They want to achieve as much as I did and they always want to learn how to be better. I’m delighted I have the chance to help them.

The feeling that has given me is making it easier to accept that my playing days are coming to an end. I would love the chance to keep on playing if it comes along. It would be perfect to find a role that combines playing and coaching, like Kolo did under Brendan Rodgers at Celtic and now Leicester. Brendan has been a fantastic mentor for Kolo and his progression in the last few years has been phenomenal. Kolo worked hard to get to where he is and I’m aware I need to learn everything and work my way up. It’s all part of the journey and it’s all really important.

Thanks to everyone who has helped me in my transition into coaching, I’m getting the chance to start doing that. And because of the opportunities I’ve had to help out young players already, I’m now looking forward to the next stage of my career. Back when I was told I could be a coach, I wasn’t at all sure. Now, though, I can see it too.

• This article was published first by The Coaches’ Voice

• Follow them on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube

[ad_2]

Source link