In a way, it was the perfect understated ending: with a short, sober statement on the Derby County website. New manager appointed at struggling Championship club. Signs a two-and-a-half-year deal after a cautiously successful stint in caretaker charge. Liam Rosenior to be his assistant.

Meanwhile – buried in the seventh paragraph, as if an entirely incidental detail – England and Manchester United’s all-time leading goalscorer has decided to retire as a footballer.

Wayne Rooney. Remember the name? Perhaps the vague whiff of anticlimax owes itself largely to the fact that Rooney has – on some level – been retiring for most of the last decade. There was the emotional departure from Manchester United in 2017. The following year, he said his goodbyes to the Premier League. There was the first international retirement. The one-off comeback, after which he went back into retirement again. And now, the final curtain. The discussion of his legacy and place in the game will continue to bubble away, and rightly so. It should be possible both to acclaim Rooney for what he achieved in the game and wonder whether he could have done even more.

Five Premier League titles and one Champions League triumph – the same as John O’Shea – do not settle the debate on their own. His goal records – 253 for United, 53 for England: gargantuan feats that will one day be broken.

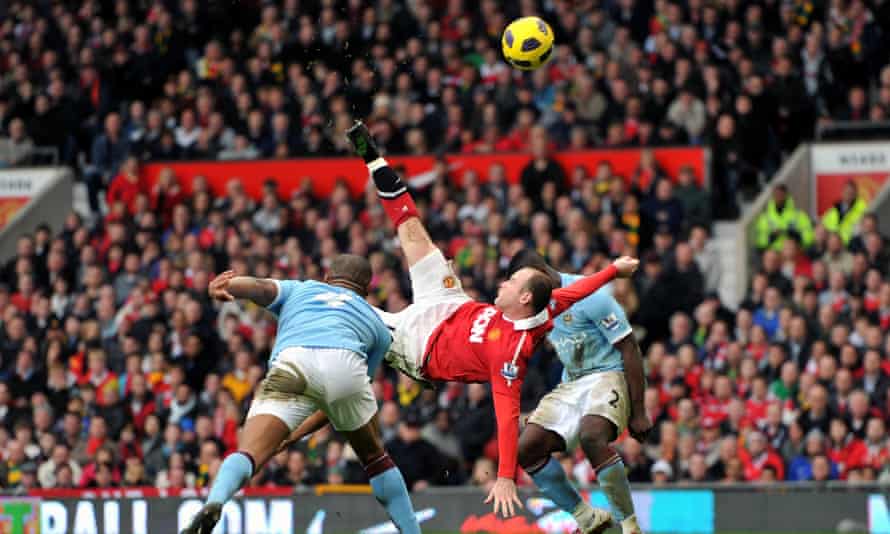

When the dust settles, what does Rooney leave us beyond lists and chunks of metal? This is, perhaps, the basic paradox of Rooney: that a player of such emotional heft will ultimately be judged largely on numbers and records, that a player who seemed purpose-built to generate unforgettable era-defining moments generated surprisingly few of them. What are the defining Rooney moments? The big performances in finals? The reality-bending wonder-goals? What is Rooney’s Istanbul 2005, his Villa Park 1999, his Euro 96, his Hand of God? Of course there was the bicycle kick against Manchester City in 2011, a heartwarming last-minute chase and tackle and assist for DC United in 2018, a couple of eye-catching goals from the halfway line. But really, the defining Rooney moment comes right at the beginning: that scene-setting goal for Everton against Arsenal in 2002 as a 16-year-old child.

Even to watch it back now is to realise how the memory plays tricks on you. The chance was created not by a barrelling run but a neat control and shuffle. The finish itself was not smashed into the top corner, but curled with the utmost guile and precision. But it was too late. Wazza – England’s slaloming, all-conquering comic book hero, a new hero for the WKD age – was born.

And so began the first age of Rooney-mania: the teenage tearaway. It took in that big-money transfer to United, a breakthrough tournament at Euro 2004 and probably ended in 2006 when Chelsea’s Paulo Ferreira fatefully broke his metatarsal, ushering in the second age: Rooney as national fixation. Yet while English football still expected Rooney to win international tournaments all on his own, and chided him when he failed to supply the required miracles, at club level he was increasingly becoming folded into a different player entirely.

The emergence of Cristiano Ronaldo at United led Alex Ferguson to wedge him into an unfamiliar wide role. He still scored 38 goals in the 2006-09 seasons, won most of the silverware he was ever going to win. But in retrospect it feels like the great leap not made, the point at which the door to the immortals slowly began to creak shut.

Into the third age, then: the long retreat. The congealment had already begun before Ferguson retired in 2013, but it was around that point when we all collectively realised that Rooney was never quite going to fulfil the white-hot promise of his early years. Successive United and England managers puzzled over how to incorporate a player who seemed both increasingly influential and increasingly tangential.

His finishing, link play and attitude were as good as ever. But did he actually help your team win? Derby felt like the logical conclusion of this process: a genius midfielder essentially spraying gorgeous passes from his armchair in the centre circle. Meanwhile, his outrun team languish in the bottom three.

It’s useful, as a thought exercise, to wonder how he might have fared had he been born Spanish or German: whether his taste for the heroic might have been chiselled into something more collective, more useful, more durable.

And yet, for all the talk of atrophy, right to the very end Rooney remained a fabulous player to watch: intuitive, eloquent and zealous, a player whose pure love of the sport was evident in every nourished touch.

He is unlikely to be as great a manager as he was a player. This is no slight on his coaching ability; simply a bald statement of probability. For every Cruyff there are a dozen Van Bastens; for every Beckenbauer a dozen Maradonas. Genius rarely photocopies itself. Rooney’s name and fame may have earned him this chance. But from here on in, he will have to survive on his wits alone.

Source link