[ad_1]

As Arsenal’s rebuild under Mikel Arteta has stalled over the past few weeks, one of the most common quick-fixes suggested has been to move Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang from the left into the middle. He’s a goalscorer, runs the argument, so you need to put him in the middle, nearer the goal. Which, frankly, is the equivalent of those Victorian doctors who believed malaria was caused by the bad air around swamps – the theory isn’t entirely unrelated to the reality, but a series of vital stages have been missed out.

However simple football played well may appear, it is not a simple game, not at the highest level – or even at the level at which Arsenal are playing, as they prepare to host Burnley on Sunday night. Scoring goals is not just about putting a goalscorer near the goal. Over the past couple of decades one of the most striking tactical developments has been the increasing diversity of centre-forwards. The days when he was a target man, a poacher or a whippet, or some combination of the three, are long gone.

Arteta tried playing Aubameyang though the centre, against Leeds and against Wolves. In each of those two games he managed one shot on target. He didn’t score. In both matches, Arsenal were dreadful. That’s not to suggest Aubameyang was wholly or even primarily responsible, poor as his form has been this season, but it is a fallacy to suggest a forward is necessarily more dangerous starting in the middle.

This was something Alex Ferguson talked about at length after he began playing Wayne Rooney wide in Champions League games in 2008. The move was initially a defensive one: Rooney could be trusted to track his full‑back in a way Cristiano Ronaldo could not and so the Manchester United manager swapped them over.

But, as he pointed out, there are certain advantages for a forward starting wide and cutting infield. Playing on the hypotenuse increases acceleration room: from a starting position high up the field, it’s easier for a forward to be travelling at pace when he gets to the box if he starts wide. Plus this has the advantage of naturally attacking the gap between full-back and central defender, usually against the weaker foot of the full-back.

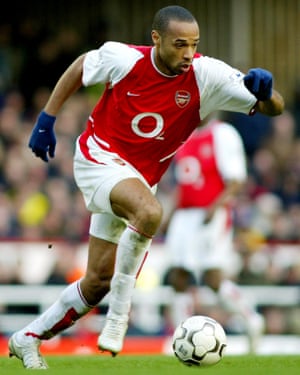

Goals from wide forwards have become an increasing feature of the game over the past decade. Lionel Messi and Ronaldo have scored a significant proportion of their vast tallies from wide starting positions – as has Aubameyang. That’s a formalisation of a movement that has been implicit in the game for far longer. Thierry Henry, for instance, was a master at pulling left and then cutting in on to his right foot.

But the most striking and consistent example is Liverpool, where Mohamed Salah and Sadio Mané have spent the past three years scoring hatfuls of goals, coming from what would once have been called inside-forward positions into the space vacated by Roberto Firmino, who has become the archetypal false 9.

Theirs is one of those glorious combinations that happens only very occasionally: the interaction of the three elevates each member of it. None of them have ever been so good, so effective, for other clubs or for their national teams. And none of them perform what might be termed a traditional forward’s role.

What Tottenham are doing is a variation on a theme. Clearly their general counterattacking philosophy is very different to that at Liverpool, but Harry Kane’s habit of dropping deep before spinning and feeding Son Heung-min follows the same basic principle that central defenders are uncomfortable following their centre-forward too far and that runners from deep are difficult to pick up, especially when they target the space behind the full-back, which these days is often almost a midfield position. Kane, meanwhile, remains a significant goal threat in his own right, far more so than Firmino.

Over the past decade, the notion the centre-forward’s role may be just as much about creating space for others as for scoring himself has become an orthodoxy. But it is certainly not the only orthodoxy. Edinson Cavani’s second-half performance for Manchester United against Southampton showed just how effective a more traditional interpretation of the role can be. Bayern Munich’s Robert Lewandowski, meanwhile, remains probably the best centre-forward in the world while resembling nobody so much as Ian Rush, a brilliant all-round finisher who is also key to leading the press.

If there is one characteristic that unites the best modern strikers it is they do not have just one characteristic. Jamie Vardy, lightning fast and adept at timing his runs behind the opposing rearguard, is in one sense a type that has been familiar since defences started playing a coordinated offside trap again in the mid-60s. But whenever Brendan Rodgers talks about him, the Leicester manager highlights neither his pace nor his finishing but his tactical intelligence and the way Vardy leads the press.

Dominic Calvert-Lewin has attributed his spurt of goalscoring this season to Carlo Ancelotti’s advice that he should be more like Filippo Inzaghi and confine himself to the penalty area. Yet Calvert-Lewin is nothing like the former Milan striker in build or approach. He has at time played wide, but what sets him apart is his heading ability: he is a terrifying amalgam of target man and poacher.

Around 15 years ago, it appeared that the future was the universal forward: Henry, Andriy Shevchenko, Didier Drogba or Hernán Crespo, players who were mobile, strong, quick and good finishers. But evolution is rarely as simple as that. Instead there has been an embrace of specialism – or, perhaps more accurately, specialisms. The best teams work because of the multiplicative effect of the interactions between players. Liverpool’s front three, or the Kane and Son partnership, are spectacular because they all complement each other. They do not conform to some pre-existing template.

To ask whether Aubameyang should play wide or through the middle is to ask the wrong question, dealing in absolutes when everything is contingent. Far more important is how the Arsenal striker’s attributes can be enhanced by the rest of the team. It is that that defines the very best.

[ad_2]

Source link