[ad_1]

That’s not good news for other newage private sector banks, which had exploited a crucial ‘gap in the market’ and built business models around nimble technology, responsiveness, and higher rates on both savings and term deposits.

It is no wonder, therefore, that since an unprecedented reconstruction of Yes Bank began earlier this month under federal watch, deposits at peers such as RBL Bank or IndusInd have fallen by 2-3% since March 6 when Yes Bank slipped into the regulatory straitjacket. PMC, too, is in dire straits with the regulator extending curbs on the bank for six more months after the restrictions had begun last September.

CAPITAL DISTRESS

“There has been a change in sentiment since March 6. We lost about 3% of mostly term deposits from PSU institutions and some companies since that date. Although our liquidity, capital and retail deposits have stayed intact, we did not sit easy in our office last week,” said Vishwavir Ahuja, CEO at RBL Bank.

IndusInd Bank has also lost 2% of its deposits, primarily because some state government institutions have pulled out funds. However, the bank has been the worst loser among the 12 banks in the Nifty Bank Index, losing 45% of its value last week.

Bankers admit things have changed for private sector banks as the faith and trust of depositors in these institutions have been shaken.

Yes Bank was not the first lender to have foundered lately. Over the years, scheduled commercial banks such as the erstwhile GTB or United Western Bank (UWB) have failed. But what is different this time is the unconventional route the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has adopted for reviving a lender whose erstwhile promoter is now in custody.

QUIET BURIALS NO MORE

During earlier failures, the sick banks were given a quick burial through a merger with larger public sector peers. This ensured that the moratorium was lifted quickly, no sign of the sick bank remained and the contagion could not spread to other lenders.

In the Yes Bank case, for reasons best known to the regulator, the moratorium was stretched to 13 days, and for the first time it was ensured that the bank survived through investments from a set of domestic peers.

Analysts say the imposition of a moratorium without having a prepared restructuring plan in place is a big reason for the contagion spreading to private sector banks.

“Over the years, RBI has put several struggling banks under moratorium and the same was followed up soon with merger announcements. In some of the cases after 2000, RBI was quick to merge these with a stronger name in a short span of two days,” Credit Suisse analyst Ashish Gupta wrote in a note.

LIQUIDITY LOCKDOWN

Gupta says the loss of access to their own money in a large bank has scarred depositors and shaken their trust in the system, something that cannot be mended overnight.

“Post the delayed Yes Bank bailout, the market has been concerned about deposit flight out of other smaller private banks, as reflected in their sharper 50% stock price correction vs 27% for other banks. IndusInd and RBL have reported a 2-3% decline in deposits in recent weeks,” Gupta said in a note last week.

Yes Bank’s struggles with capital over the last one year have been well documented. As a result, some depositors had already started pulling their money out of the bank.

In the six months before the moratorium was imposed, the bank lost 34% of its deposits. Total deposits fell to Rs 1.37 lakh crore in December 2019 from Rs 2.09 lakh crore in September 2019.

STRAW THAT BROKE THE CAMEL’S BACK

However, a directive by the Maharashtra government not to keep savings in private sector banks seems to have been the last straw for private sector lenders.

Both IndusInd and RBL have lost some public sector term deposits in the last fortnight.

“We have lost deposits in Maharashtra because of the notification by the government,” said IndusInd Bank CEO Sumant Kathpalia, but added that the bank is strong enough to tide over this crisis. “We believe that we are very strong in government business. About 20% of our business comes from there and that’s a very healthy trend. It is spread over different states. We are still highly liquid and today also we are lending in the call market, which would not be possible if we were not highly liquid,” Kathpalia said.

A CLEANER BILL OF HEALTH

Questions on these lenders emerge even as there has been no deterioration in their financial health over the last quarter.

None of these lenders have been placed under any restrictions by the RBI. In fact, out of the six lenders placed under prompt corrective action (PCA) of the RBI, only one, Lakshmi Vilas Bank (LVB) is a purely private sector bank. Four other staterun banks — Indian Overseas Bank (IOB), Central Bank of India, UCO Bank and United Bank of India — are under this framework, which puts several restrictions on them, including on lending, management compensation and directors’ fees. The LIC-controlled IDBI Bank is classified as private sector bank but it is owned by a government entity.

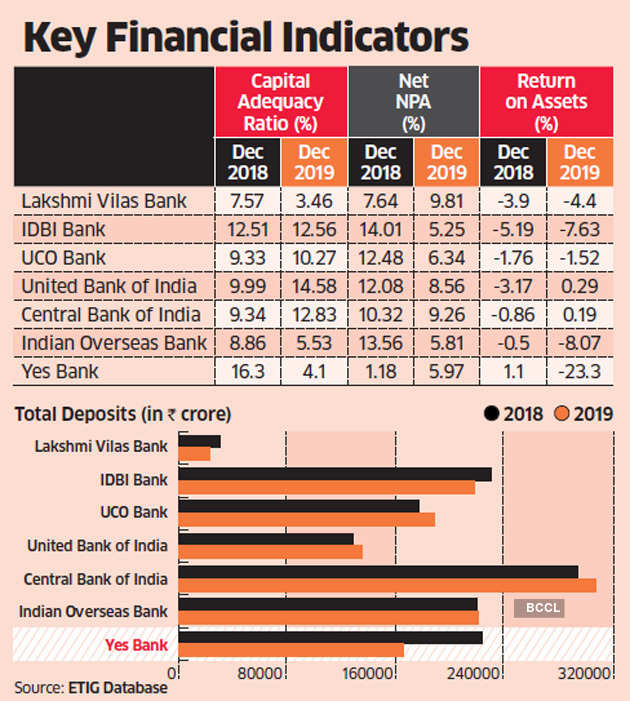

The RBI tracks three specific parameters for a bank to be brought under PCA. A bank’s capital adequacy ratio (CAR) should be below 9, net NPAs over 10% and return on assets (RoAs) less than 0.25%.

Four out of six PCA banks have a negative RoA and though net NPAs for all these lenders is below 10%, CAR for two of them — LVB and Indian Overseas Bank — is at 3.46% and 5.53%, much lower than the mandatory requirement of 9%.

By contrast, private sector banks such as IndusInd, RBL, Federal, Karnataka, South Indian and Kotak Mahindra have CAR above 12%, RoA above 0.25% and net NPAs much below 6%.

Despite this, public sector banks are sitting pretty in terms of deposits as savers see an invisible sovereign guarantee behind these lenders.

WORK IN PROGRESS

The problems for private sector lenders may have been compounded by the Yes Bank collapse but they are more to do with basic banking issues. The problems are not to do with building assets but getting more granular deposits and reducing dependence on top depositors.

“Making deposits more granular is a work in progress. We have come a long way from 8-9% CASA when we took over, to 27% now and target to take it to 30% by the end of the next fiscal. Though we lost about 3% government and institutions’ deposits, our retail deposits have stuck with us,” Ahuja said.

However, analysts say the perception about private sector banks will not change overnight. Together with communicating their positions over the last week, there is a need to change their business models.

“May be these banks have to engage more with government agencies to build trust. One way to do that is to participate in state government auctions, which private sector banks are usually reluctant to do. Transparent and timely disclosures will of course help a great deal,” said former RBI deputy governor HR Khan.

But the burning issue now is to contain the spread of Covid-19, and prevent private banking from falling off the cliff.

“What the Yes Bank issue has again proved is that depositors’ money is safe and no scheduled bank has been allowed to go down in India. But with what is happening on the ‘biological’ side, there will be changes in banking. We will see more digital banking and lending will be much more based on risk and rating,” said Aditya Puri, MD at HDFC Bank.

[ad_2]

Source link