[ad_1]

But the new RBI regime under Shaktikanta Das has been different. It has already allowed banks to extend the MSME loan recast scheme and allowed restructuring of loans to the real estate sector.

“The RBI announcement of forbearance towards stressed sectors signifies a gradual shift away from the regulator’s earlier efforts to enhance the quality and transparency of asset classification in the Indian banking system,” said Saswata Guha, director, financial institutions, Fitch Ratings. “There is a risk that such regulatory forbearance will perpetuate moral hazard, as it follows aggressive lending growth and risk-taking in certain sectors.”

Indian banks have a poor track record with restructuring. The RBI’s asset quality reviews in FY16 and FY18 found that a dominant share of loans restructured after FY12 degraded into non-performing loans (NPLs), according to a Fitch analysis.

BLOW HOT, BLOW COLD

“You are encouraging bad behaviour by supporting it and demoralising the ones with good behaviour; this is akin to farm loan waiver that leads to bad credit behaviour,” said Kuntal Sur, partner – financial risk & regulation, PwC. “This is nothing but kicking the can down the road, this should not be encouraged.”

The concept of regulatory forbearance arose when the RBI allowed project loans to retain their standard asset classification on extension of their repayment schedule in May 1999. This was extended to treatment of restructured accounts in March 2001 under the Corporate Debt Restructuring (CDR) mechanism, for restructuring of debt without the need for an asset quality downgrade if the restructuring plan met certain conditions. For years, asset quality forbearance was used more as a tool for avoiding recognition of defaults and less for their effective resolution.

In 2008-09, after the global financial crisis, the RBI agreed to forbear on certain kinds of stressed loan restructuring, hoping that this was a temporary need pending stronger growth. Unfortunately, for a variety of reasons, the stress has not been temporary, and growth in these sectors has proved elusive. This regulatory forbearance was made available to all types of loan restructuring except commercial real estate exposures, capital market exposures and personal and consumer loans.

Since 2008, RBI relaxed norms for restructured loans several times and allowed lower provisioning for select categories of loans. Its regulatory relaxations prevented a rise of nearly Rs 90,000 crore in NPAs. These relaxations include allowing unsecured loans to microfinance companies to be restructured in 2011, and allowing second restructuring of loans on a case-to-case basis. State electricity boards and the aviation sector are two notable examples wherein loans were restructured for a second time, but were not classified as non-performing assets. But, in May 2013, the RBI announced the decision to withdraw forbearance on asset classification effective April 1, 2015. Shortly after this, the RBI began its Asset Quality Review (AQR) exercise to determine the “real” stock of the bad loan problem.

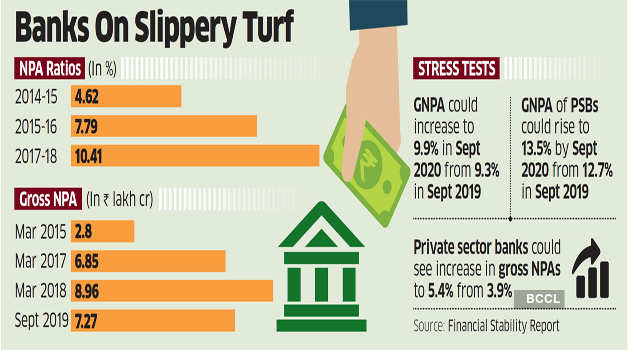

After the RBI undertook the AQR that led to recognition as NPA of several loans, which banks had then considered to be standard assets, NPAs went up from 4.62% in 2014-15 to 7.79% in 2015-16, and were as high as 10.41% by December 2017.

However, in the wake of mounting NPAs, the RBI allowed asset classification benefits for certain types of restructuring schemes. These included Strategic Debt Restructuring (SDR), Flexible Structuring of Project Loans and the Scheme for Sustainable Structuring of Stressed Assets (S4A).

HARD TIMES

A revival in GDP growth rate is key to the Indian economy, which has slowed to an 11-year-low of 4.5% in the September quarter. Bank of America’s India Activity Indicator slipped to 3.1% in December from 4.5% in November. The Index of Industrial Production for December shrunk to 0.3% while retail inflation rose to 7.59% in January.

“It is not surprising in the current weak operating environment and is in line with a recent trend to weaken asset recognition standards,” said Guha of Fitch. “These extensions are only likely to defer asset-quality pressures unless there is a sustained improvement in macroeconomic conditions. Most of these sectors have had above-average lending growth in the last few years, either directly or indirectly via non-banks, and could be at risk were the economy to slow. Moreover, these measures are unlikely to support sustainable credit growth until capitalisation improves meaningfully across banks, in particular among state-owned banks, which account for nearly twothirds of the sector’s assets.”

The MSME sector accounts for over 28% of GDP, more than 40% of exports, while employing approximately 110 million people. The outstanding banking sector credit to MSMEs was Rs 15.11 lakh crore while its gross NPAs were 5.8% of the total credit. Likewise, the real estate sector has been in trouble for quite some time and is the primary reason behind the sustained nonbank lending crisis.

“In extreme situations, the economic value of not taking any action is too high,” says Sur. “If you look at the government’s perspective, we are in a slow growth phase; if you allow further defaults, the negative impact could bring down the growth further.”

Some believe that difficult times warrant some degree of forbearance, some hand-holding to performing and otherwise viable units in tiding over temporary difficulties. But even RBI data shows that restructuring has been often used by banks for ‘evergreening’ problem accounts, thereby just postponing the recognition of a problem.

“Forbearance may be a reasonable but risky regulatory strategy when there is some hope that growth will pick up soon and the system will recover on its own,” Rajan had said in July 2016. “Everyone – banker, promoter, investors, and government officials – often use such a strategy because it kicks the problem down the road, hopefully for someone else to deal with. The downside is that when growth does not pick up, the bad loan problem is bigger, and dealing with it is more difficult.”

INSOLVENCY RESOLUTION

Central bankers on many occasions in the past have said that restructuring schemes were required because India did not have an effective bankruptcy law in place. In 2016, the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC), which is a comprehensive bankruptcy code, was enacted and notified. The Code envisages timely resolution of borrower defaults through collective decision making by the creditors. But, the success of the law is yet to be proven.

“The general approach of bankers to stress in large assets has been one of avoiding the de jure recognition of non-performance of such accounts,” NS Vishwanathan, RBI deputy governor, had said earlier. “This is why we have a history of a large number of cases of failed restructuring as the schemes were used for avoiding a downgrade rather than resolving the asset. Prolonging the true asset quality recognition suited both the bankers and borrowers.”

As per the latest data from the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India, 58% of all closed cases under bankruptcy to date were via liquidation while only 14% of cases were resolved with an average haircut of nearly 57% on admitted claims.

ENCOURAGE GOOD BEHAVIOUR

“Good practices should be encouraged so that there is incentive toward credit discipline. What is the guarantee if the economy goes from bad to worse, these loans will be repaid,” says Sur. “Banks have taken excessive risk in the past which is why we are seeing encouragement of bad behaviour.”

While many say that the RBI move is intended to improve monetary transmission, provide credit support to fields that have multiplier effects within the wider economy, the regulator should also bring in rules to reward those with better credit discipline. The regulator is also aware of the risks that the relaxations bring in, but places the onus on banks to ensure that their books don’t have a hole.

“Sector-specific pockets of stress need policy attention,” Governor Das said at a conference this week. “At the same time, proper due diligence and risk pricing in lending are of prime importance so that the health of the banking sector is not compromised while ensuring adequate flow of credit to productive sectors of the economy. Timely mitigation measures like faster resolution, better recovery, etc, need to be continued to bring down gross nonperforming assets.’’

[ad_2]

Source link