Business reporter

Saab

SaabWar, cross-border conflict and geopolitical upheaval are rarely deemed good for business.

Yet that appears to have been the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on two of the aggressor’s neighbours to its west – Finland and Sweden.

Not directly, of course. Rather, it was the two Nordic nations’ response to the invasion that turned fear into hope.

Both countries applied for membership of the Western defence alliance Nato in May 2022, some three months after the winter invasion.

Less than three years later, they’re both full members and already reaping the benefits, in terms of both national security and economics.

“We’re no longer a country that cannot be trusted,” observes Micael Johansson, chief executive of Swedish defence company Saab, in reference to the nation’s previous historic neutrality.

He points out that in the year since Sweden joined Nato in March 2024, Saab has already negotiated framework agreements with the Nato Support and Procurement Agency (NSPA). The NSPA is the body that organizes Nato’s ordering from defence firms.

Mr Johansson adds it is now much easier to gain insights into what’s going on inside the alliance. “We couldn’t access NSPAs before,” he says.

Jukka Siukosaari, Finland’s Ambassador to the UK, agrees. “Being part of Nato brings us on an equal footing with all the other allies. It enlarges the possibilities for Finnish companies in the defence sector and beyond.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesPrivate companies will benefit from pledges by Nato member states to increase defence spending.

Presently, only 23 of the organisation’s 32 member states currently meet a defence spending target of 2% of GDP, but ambitions have grown in recent months, only to surge in recent weeks and days amidst plenty of turbulence within the alliance.

Amidst uncertainty about what Nato might look like in future, there is no doubt that these higher spending commitments will remain and perhaps even strengthen if Europe was to decide it could no longer rely on the USA.

Nato’s newest members’ spending commitments are already ahead of those expressed by several existing members. Last year, Finland spent 2.4% and Sweden 2.2% of their respective GDP on defence, and both aim to raise this to between 2.6% and 3% in the next three years.

Examples of new Nato initiatives on Europe’s northern flank include the establishment of new Nato bases, and efforts to establish joint defence forces, in northern Finland.

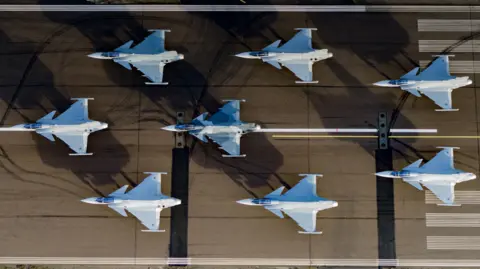

Plus the formation of The Joint Nordic Air Command, which brings together Finland’s, Sweden’s, Norway’s and Denmark’s 250 front-line combat aircraft under a joined up command structure, with flexible basing and backed by shared intelligence.

In addition, substantial investments will be required to replenish stockpiles of advanced weapons systems, including missiles and anti-tank systems, Mr Johansson points out.

And while the White House this week announced a pause in US military aid to Ukraine, European leaders have declared they’re in it for the long haul, so here too we can expect substantial and ongoing spending on arms.

Aerial surveillance programmes and underwater systems are also increasingly in demand as the returning tension between Russia and the West brings a new chill to the Arctic region.

In these areas Saab’s boss is eager to promote its own solutions, such as the GlobalEye airborne early warning and control platform, and its Sea Wasp, a remotely-controlled underwater vehicle that can neutralise explosive devices.

Yet given Donand Trump’s strong emphasis on “America first”, it is unlikely that he will be happy with European Nato members choosing Saab, or indeed any other European defence firm over US rivals.

Europe will need to balance its desire to reduce its reliance on the US with their obvious need to retain American support.

European members will also need to consider Nato’s defence systems’ complexities and interdependencies. They often combine technologies and machines, weaponry and ammunition, vehicles, crafts and vessels, that are produced in several different Nato countries.

In a sense, then, the alliance is held together by complex supply chains and contractual agreements that could not possibly be untangled overnight.

“Europe’s Trans-Atlantic relationship will always remain important,” says Mr Johansson, though he also points to a “growing realisation in Europe that we have to do more on our own”.

Getty Images

Getty Images“The US really protects its own defence industry, and we should do the same in Europe,” he says, as he welcomes “fierce competition” between commercial defence companies.

Much of this competition may be between relative newcomers to the defence industry, however.

Finnish government agency Business Finland has published a guidebook that offers advice to companies on how to do business with Nato.

Its authors predict that the armed forces on both sides of the Atlantic will have “significant new needs for services and equipment, both hi-tech and low-tech”.

Many of these needs will need to be met by start-ups and established small to medium-sized companies, says the guide, rather than exclusively by large, established defence companies.

Johan Sjöberg, security and defence policy advisor at the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise, says Nato membership has opened doors for Swedish companies, not least because “the perspective of other countries and companies [towards them] has changed”.

Mr Sjöberg adds that he favours a “holistic view, that security is good for business, as increased security and stability provide long-term credibility”.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn Finland too, Nato membership has created new opportunities, especially for the plethora of small and medium-sized companies that Ambassador Siukosaari refer to as “Nokia-spin-offs”.

These are expected to increasingly provide cutting edge tech, such as drones, sensors and digital surveillance systems for programmes such as the Norway-to-Poland “drone wall” that six Nato members are developing to defend their borders with Russia.

Indeed, as the nature of warfare changes, Europe’s security may increasingly rely on cyber-defence and the protection of civilian installations such as systems-critical seabed pipelines and cables.

But perhaps the most revolutionary idea to emerge from Nato’s Nordic expansion is the region’s “Total Defence” concept.

Also applied by Norway and Denmark, it considers national infrastructure such as the internet and telephony, energy generation and distribution, road networks, and secure supplies of food, medicine as parts of a total defence system.

Much of this may not be registered as defence spending in the statistics, but at the same time, none of it is free.

Beyond the civilian infrastructure spending, national military service, for instance, sometimes takes people away from the economically productive parts of the economy, Ambassador Siukosaari points out.

But perhaps what they deliver does more for the nation than mere provision of products and services?

Nato’s newest members believe they could teach other allied countries a thing or two about defence. They clearly offer new perspectives both on how defence spending should be measured. And perhaps also on how civilian society and private enterprise can play their parts.

Source link