[ad_1]

The big picture: It’s rare to see mainstream news stories about challenges involving the semiconductor industry, but when some automotive manufacturing plants in the US were recently shut down because of a shortage of chips, suddenly everyone wanted to understand why. The reporting that went into those stories ended up shining a light on little understood areas of business, such as automotive and tech industry supply chains, as well as companies that weren’t widely known, including US-based chip manufacturer GlobalFoundries.

Along the way, the media and politicians became acutely aware of the challenges facing US-based semiconductor manufacturing, as well as how dependent even seemingly traditional industries had become on chips and digital technologies.

Quite a few of them discovered that GlobalFoundries was a critical supplier to numerous automotive companies. What many didn’t really figure out, however, is exactly why that is the case. Part of the reason is that the connection is a complex one that, to fully understand, requires digging into the details of how and why these automotive technology supply chains exist in their current state, as well as how some key chip process technologies work. That’s not something that’s going to be appealing to a mainstream audience.

What’s even more interesting than these essential elements, however, is to see how these business relationships are continuing to advance and what those changes says about the evolution of the entire automotive industry.

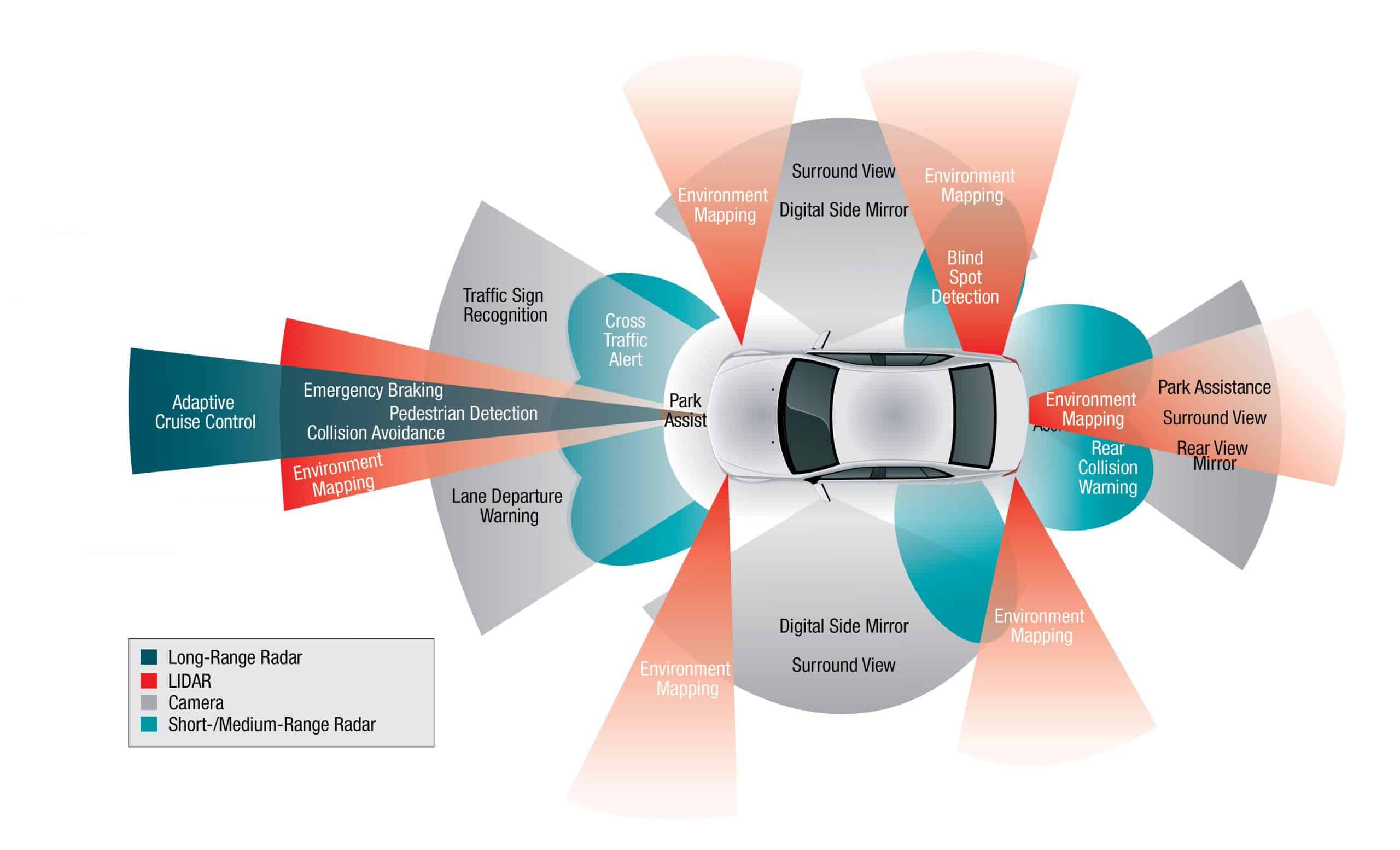

Case in point is a newly announced deal with Tier 1 supplier Bosch working directly with GlobalFoundries (GF) to develop a new radar chip focused on ADAS (Advanced Driver Assistance Systems) applications. Bosch has designed an SoC (System on Chip) using millimeter wave technology—yes, similar to what’s used for 5G—that will be built using GlobalFoundries’ 22FDX RF manufacturing process.

A bit of additional context will explain why this seemingly basic announcement is much more important than it initially appears. First, it helps to understand that today’s automotive supply chains are enormously complex.

There are multiple layers, or “tiers,” of suppliers who contribute different subsystems of a car (such as the infotainment system, the climate controls, the assisted or autonomous driving features, etc.) that automakers then piece together into various car brands, with some elements able to be used across multiple brands, while others remain unique to a particular brand.

Beneath the tier 1s, are tier 2 and tier 3 suppliers who sell components that go into those higher-level subsystems. Some of these tier 2 and 3 suppliers are semiconductor manufacturers, like NXP and Renesas, who make chips for the various ECUs (electronic control units) that, as their name suggests, “control” these various subsystems. Many of today’s most advanced cars have over 100 ECUs (some may be as simple as controlling windows and mirrors) and even low-end cars typically have 30 to 40 of them, making cars significantly more reliant on chips than most people realize.

In the case of the recent shortages that led to production shutdowns, the problem was that when car orders tanked immediately after the pandemic hit, car makers dramatically cut their orders. When they did that, chip suppliers shifted their manufacturing capacity to components for all the other high-tech devices whose sales soared during the pandemic. Then car sales started picking up and automakers went back to these chip suppliers (many of whom never had direct relationships with the carmakers, but instead with Tier 2 and Tier 1 suppliers) and asked for more. Unfortunately, automotive parts had been moved to the back of the priority line, particularly because some of these automotive chips were low margin, and it isn’t a fast process to switch production lines back.

The automotive industry has finally started to endure the impact of technology consolidation, not unlike the early days of the smartphone.

The automotive industry has finally started to endure the impact of technology consolidation, not unlike the early days of the smartphone. Back when Nokia was king of the cell phone world, they too acted as consolidators of multiple different individual components—in their case, a radio unit, a main processor, an audio chip, display controller, analog-to-digital convertors, etc.—typically with two or three different suppliers of each element. However, when most all of those components were consolidated into a single SoC—such as what Qualcomm has done with its Snapdragon line—the whole industry was turned upside down.

As a result, we ended up with modern smartphones—and an entirely new group of smartphone makers. Driven by companies like Tesla, who could start their designs from scratch with more advanced components and, just as importantly but much less understood, didn’t have the company structure that encouraged automotive designs that were based on piecing together different components, the car and truck industry is experiencing conceptually similar disruptive innovations.

Going back to the Bosch-GF announcement, one of the several interesting aspects of the deal is that Bosch essentially short-circuited the multi-tier supply chain and took their own design straight to a chip manufacturing partner in GlobalFoundries. Just as innovative smartphone suppliers discovered, the only way that forward-looking automotive suppliers can make a meaningful impact is with unique technologies and core-level intellectual property (IP) of their own. Merely integrating other people’s technologies is no longer good enough, so Bosch chose to bring their own IP to life with this new design.

From a GlobalFoundries perspective, the fact that Bosch chose to go with them versus other suppliers with more advanced (read, smaller) process nodes, speaks not just to the growing diversity in chip suppliers, but how increased specialization in semiconductors is becoming essential.

GloFo made a strategic, but somewhat controversial decision nearly three years ago to stop pursuing smaller chip manufacturing and instead focus on more specialized techniques, such as FD-SOI (fully depleted silicon on insulator), which are significantly less dependent on transistor size.

For an industry that’s been seemingly obsessed with the idea of shrinking the size of transistors ever since it began, the idea of stopping at 12 nm struck some as nearly heretical. What many didn’t realize, however, is that techniques like FD-SOI—which integrates a thin layer of insulating material right beneath the silicon transistor, meaning the silicon is nearly on the insulator—are ideally suited for a number of different and now quite popular applications, such as RF (radio frequency) and other analog-driven designs, including automotive radar.

The basic raison d’etre for FD-SOI is to reduce the amount of electron leakage that typically occurs on mainstream chips as they are reduced in size, while at the same time reducing power consumption. One of the critical real-world benefits of the chip’s structure is that it allows analog components embedded into the design to generate signals that are cleaner and more powerful—two characteristics that are ideally suited to transmitting (and receiving) analog signals like radio waves used with smartphones and radar systems.

The automotive industry is going through some dramatic transformations driven by the fundamental shift in how cars are being designed.

GF’s 22FDX is their unique take on FD-SOI technology, produced at a 22nm process node in their factory in Dresden, Germany that appears to meet the demands of Bosch 70 GHz mmWave-based radar quite well. Apparently, another aspect of the deal is that GF is the only chip manufacturer with mmWave testing capabilities on site—whether it be for the 24-39 GHz range used for 5G mmWave phones, or the higher 70+ GHz range used for radar. On-site testing makes chip verification easier, which should make the ongoing production process faster and more efficient.

The automotive industry is going through some dramatic transformations, driven not only by the pandemic, but also by the fundamental shift in how cars are being designed. This, in turn, is leading to a rethinking and recasting of the relationships between car makers and their tech suppliers, as this recent GF/Bosch deal illustrates. Looking even further ahead, however, it’s clear we’re just at the beginning of what promises to be a long and eventful upheaval in the world of automotive technology. It’s going to be fun to watch.

Bob O’Donnell is the founder and chief analyst of TECHnalysis Research, LLC a technology consulting firm that provides strategic consulting and market research services to the technology industry and professional financial community. You can follow him on Twitter @bobodtech.

[ad_2]

Source link