[ad_1]

Seeing your favorite PC and home console games run on a tiny handheld machine is always paired with that “wow” moment of sheer admiration for the technology that makes such a feat possible. One such watershed moment in my personal gaming journey was seeing Disney’s Aladdin and Tony Hawk’s Pro Skater run on a Nokia 6600 – two incredibly cool moments that showed me that home console games can, in fact, be played on the go.

But for decades, handheld gaming machines lagged a few generations behind their home console and PC counterparts in terms of performance. And while oodles of brilliant games specifically made for handhelds are part of gaming history, handheld-centric gamers were often short-changed with inferior versions of “big screen” games that had very little, if anything, in common with their home console and PC equivalents.

The dream was always to play the latest AAA titles on the go without sacrificing anything aside from graphical details. Handheld gaming PCs have made that dream a reality. However, the journey to the Steam Deck and its ilk is dotted with dead ends, broken promises, unrealistic expectations… and some pretty cool and sometimes impractical handheld gaming machines.

The first leg of this journey began at the turn of the millennium when Sony released a tiny laptop featuring a design that would inspire the first generation of handheld gaming PCs.

Laying the Foundation

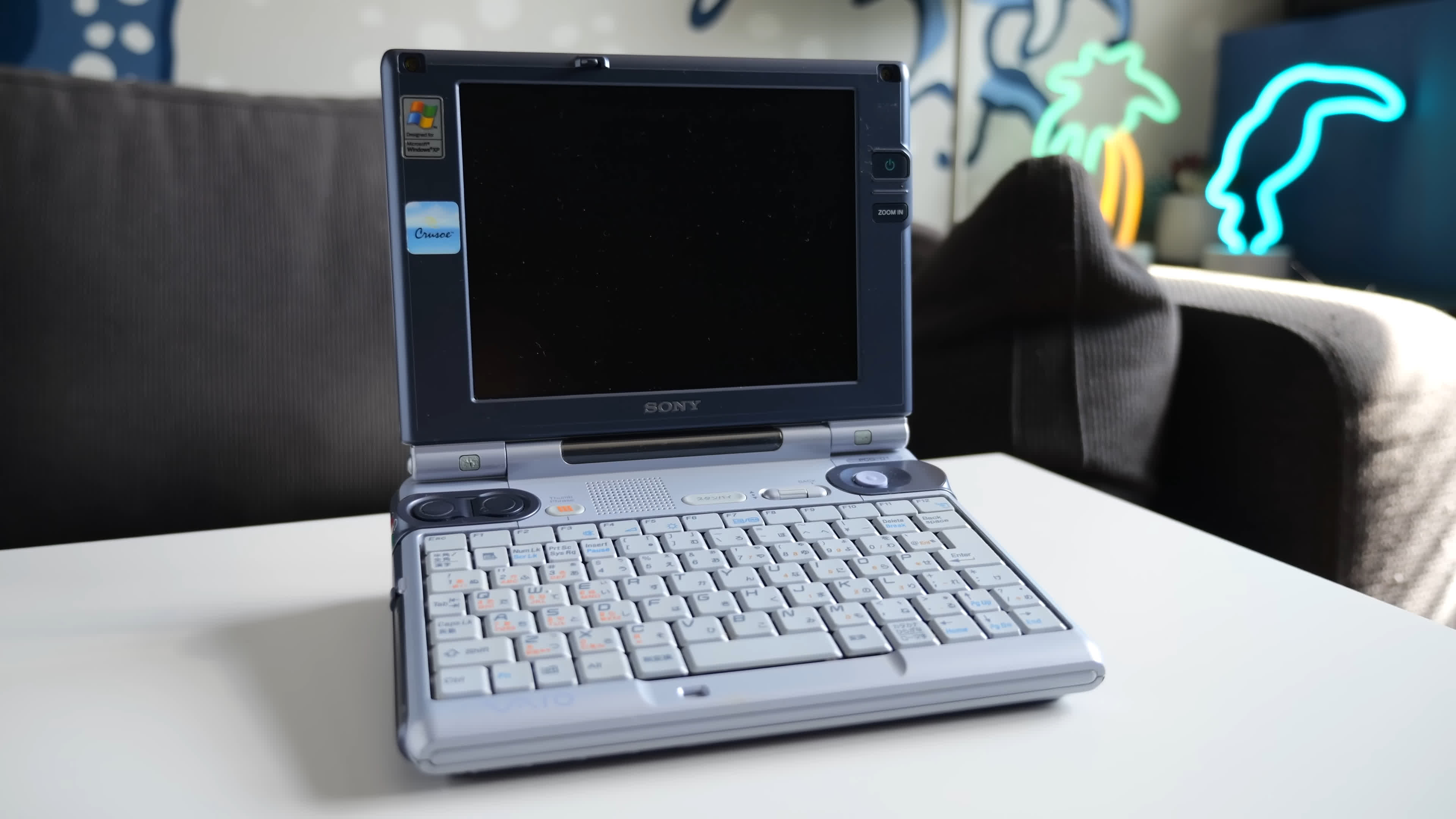

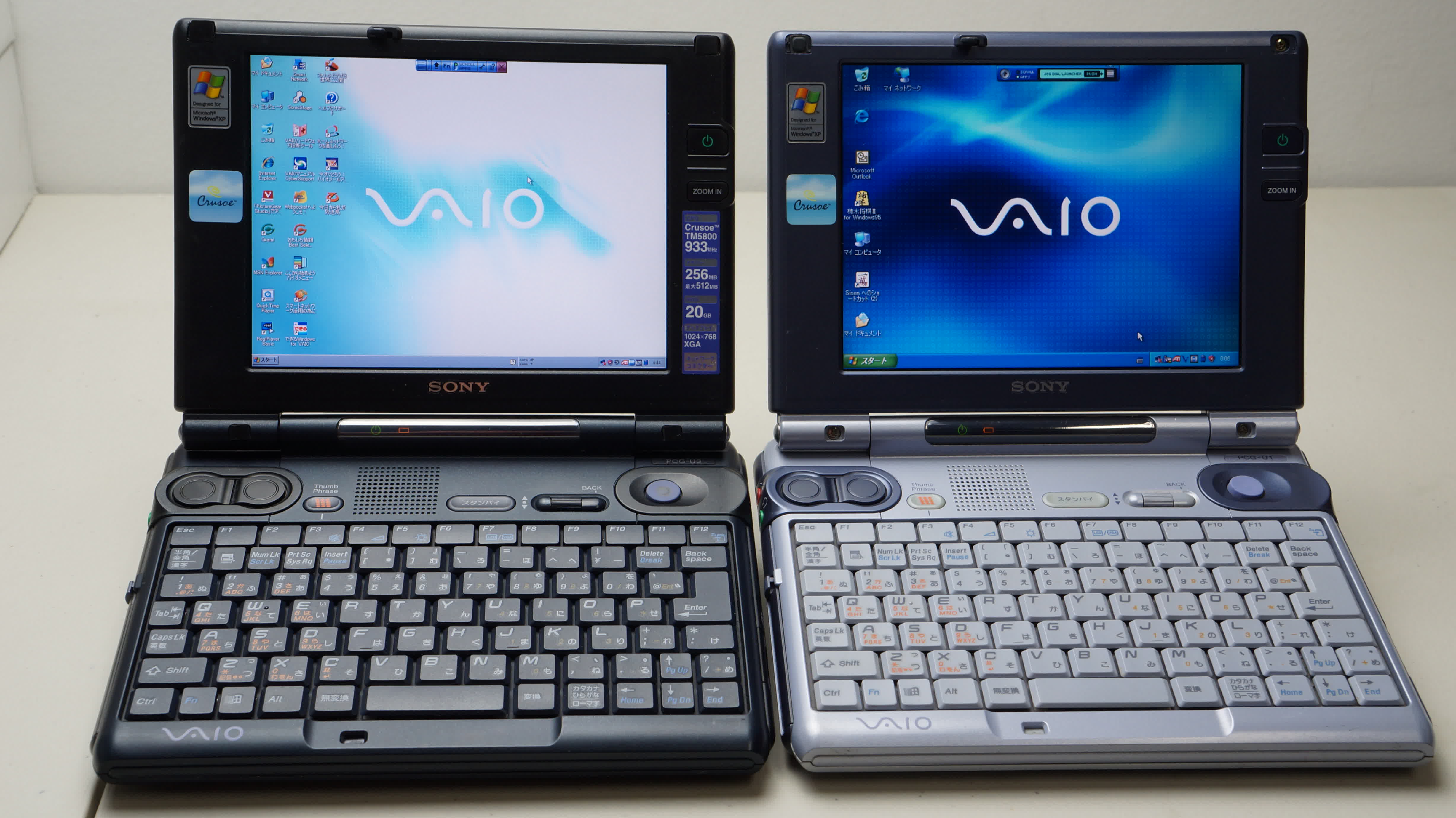

While Sony had been a prominent manufacturer of a then-novel class of subnotebooks, the company’s VAIO PCG-U1, launched in 2002, was so compact that it was regarded as a handheld notebook.

While definitely not a gaming device, it can be considered the last universal common ancestor of the handheld gaming PC family due to its unique placement of the mouse joystick and buttons, which were perfect for using the device while holding it in your hands – unlike the Toshiba Libretto series. The VAIO PCG-U1 and its successors provided a blueprint for the first generation of clamshell handheld gaming PCs that would appear less than a decade later.

The next few years were devoid of intriguing developments until Bill Gates shared the first details about Microsoft’s ultra-mobile PC concept during his speech at 2005’s WinHEC.

The UMPC initiative, then known as “Project Origami,” ignited hopes that we would finally get a handheld computer capable of playing current AAA games. This excitement was sparked by a leaked video of the project showing a tablet-like device playing Halo in early 2006. However, these hopes were dashed when the AP published a report quoting a source “close to Microsoft,” who stated that Origami wouldn’t have “advanced entertainment capabilities.”

A few weeks later, at CeBIT 2006, Microsoft unveiled the UMPC initiative, confirming their extremely limited gaming capabilities. Although the UMPC story was short-lived and unsuccessful – due to the high price of most models, niche appeal, and the rise of the smartphone – it did plant the idea of an x86-based PC optimized for handheld use and equipped with a full-fledged Windows OS into the mainstream PC hardware community.

Before UMPCs, the handheld form factor was reserved for PDAs, PC-like handhelds based on stripped-down versions of Windows, humble ARM-based hardware, and occasional niche tablets running full-fledged Windows. However, the UMPC era demonstrated that handheld PCs don’t have to be software-limited and can run any software their laptop and desktop counterparts can. While Sony first achieved this with the Japan-exclusive VAIO PCG-U1, Microsoft spread the idea globally.

During the UMPC era, a South Korean company called GamePark Holdings was revolutionizing handheld game consoles with a device called the GP2X. Founded by former employees of GamePark – the manufacturer of the GP32, a South Korean version of the Nintendo Game Boy Advance – GamePark Holdings aimed to create an open-source successor to the GP32. The GP2X was unique in that it came with an open-source OS based on Linux, resulting in a plethora of homebrew software for the GP2X, with a major focus on emulators. Unlike the PSP, which also hosted fantastic emulators, the GP2X did not impose any restrictions on its users.

This combination made the GP2X a dream machine for many homebrew software developers, turning the handheld into a cult-classic portable console despite its lack of commercial games.

GamePark Holdings would release another niche yet legendary handheld console, the GP2X Wiz, in 2009. The Wiz was an open-source emulation powerhouse and one of the earliest examples of a retro handheld console, a product category that has become quite popular in recent years. These two devices garnered significant interest from the emulation community. Three GP2X community members would go on to start their own open-source handheld console project, creating the first proper handheld gaming PC known as the Pandora.

Before we move on, here’s a showcase of some remarkable devices of this era:

Sony Vaio PCG-U1

Image credit: u/johnblade87

The adorable Sony Vaio PCG-U1 was at the forefront of the subnotebook class of products when it launched in 2002. It was a UMPC before UMPCs were a thing, and its design was a major inspiration for the Pandora and GPD Win, both of which took the Vaio PCG-U1’s mouse “thumbstick” design and transformed and refined it to fit the gaming-centric intents of the two devices.

Thanks to the position of the thumbstick, which resided on the upper right side above the keyboard, along with the left and right click buttons on the left, the PCG-U1 was optimized for use while being held in both hands. In other words, it was the first proper handheld PC, featuring a full version of Windows, x86 compatibility, a full keyboard, and an impressive 6.4-inch 1024 x 768 display.

The device was exclusive to Japan, where it earned notable success thanks to its small footprint, which was perfect for Japanese businessmen who often worked on their projects during their train commutes. Its gaming capabilities were extremely limited due to being powered by a unique Transmeta Crusoe CPU running at 867MHz, which was x86-compatible even though the x86 instruction set wasn’t implemented at the hardware level. Instead, the CPU used a virtual machine to emulate Intel’s x86 instruction set.

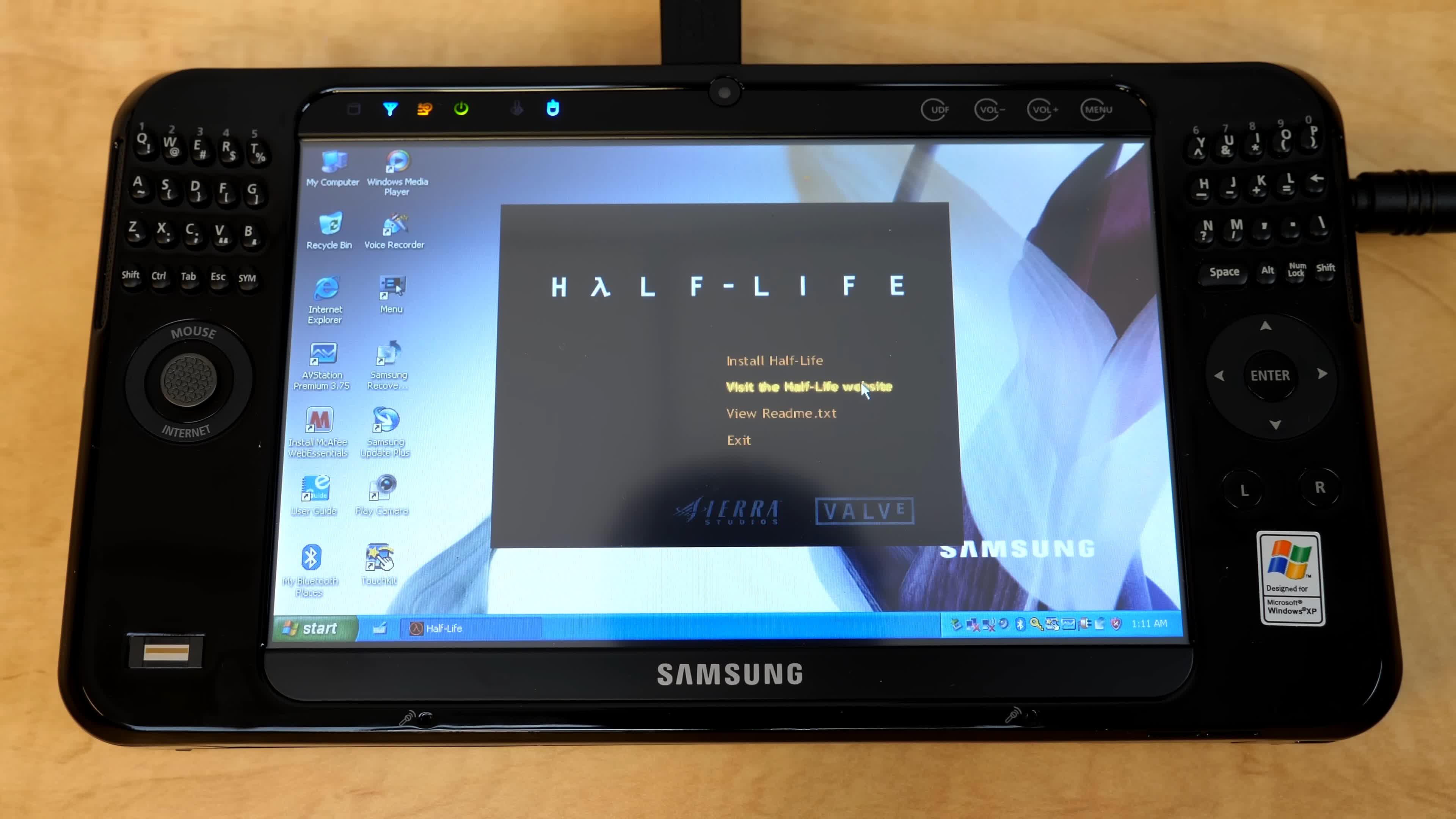

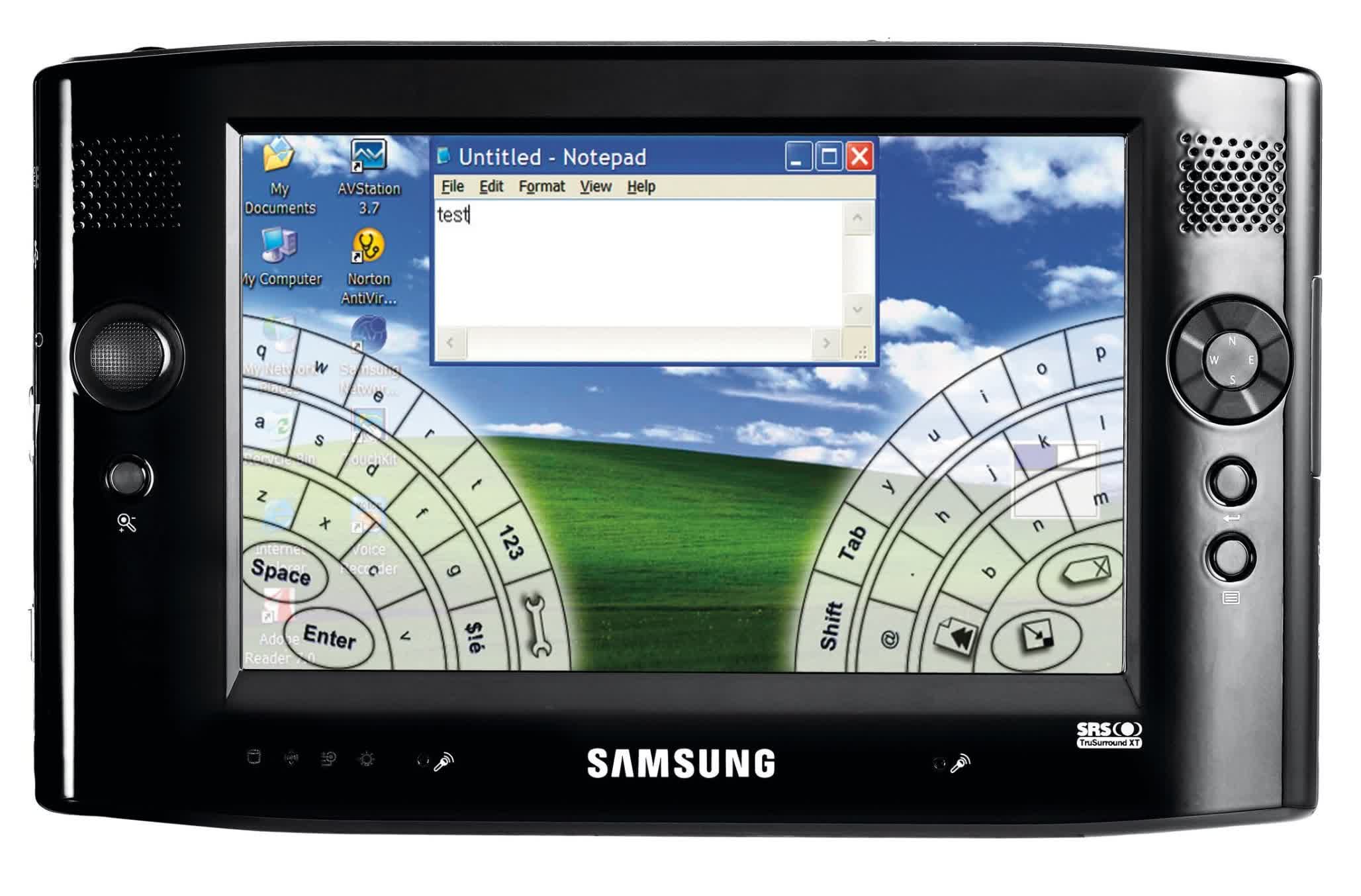

Samsung Q1

The poster child of Microsoft’s push for UMPCs, the Samsung Q1, was a proper high-end, handheld computing device. The first generation had limited usability due to the lack of a physical keyboard, but the Intel Celeron M CPU clocked at 900MHz, combined with 512MB of memory, provided a pleasant Windows XP experience, including content consumption and web browsing. The gaming capabilities were seriously hindered by the Intel Extreme Graphics iGPU, which was anything but extreme.

The second generation brought a plethora of upgrades, the most important of which included a full QWERTY physical keyboard, greatly improved battery life, and 1GB of memory. The screen remained the same size, but the 7-inch panel in the Q1 Ultra sported a resolution of 1024×600 compared to 800×480 in the original model. More expensive versions of the Q1 Ultra also included Windows Vista instead of XP, with a premium model even coming with an SSD.

The upgraded version was quite capable of running games, including Half-Life and classic isometric RPGs, but the placement of the mouse joystick on the left side and the arrow keys on the right wasn’t great for the former, as well as most other shooters.

On the other hand, the device was perfect for playing isometric RPGs and 2D platformers thanks to the left-hand joystick, touch screen, and full QWERTY keyboard. Still, the $799 price point of the base Q1 Ultra model, which ballooned to $1,499 for the high-end SKU, prevented the Samsung UMPC from becoming popular among gamers or professionals in need of an ultra-compact Windows PC.

Wibrain B1

Image credit: gigglehd

The Wibrain B1 was overshadowed by the Samsung Q1 both in press coverage and popularity, but this tiny UMPC delivered the best usability out of all UMPCs thanks to the inclusion of an actual touchpad that, combined with a split physical keyboard and a compact 4.8-inch touchscreen allowing for super easy navigation around Windows XP.

Sadly, the underpowered VIA C7M CPU prevented the tiny device from topping out any performance charts, which also meant it wasn’t capable of running many games. Still, the unique form factor and the best solution for navigating the Windows environment compared to its peers were enough to put it on this list. If it had been more popular, maybe early handheld gaming PCs would have also incorporated trackpads on top of their game controller setups.

GP2X

While the GP2X wasn’t the first Linux-based handheld focused on emulation – the title belongs to its predecessor, the 2001 GP32 – the 2005 GP2X was the first to achieve success outside South Korea and beget a small but faithful international homebrew community, most prominent members of which would years later create the first actual handheld gaming computer, the Pandora.

The GP2X had a dual CPU setup at its heart, consisting of a 200 MHz ARM920T CPU and a 200 MHz ARM940T coprocessor. The total amount of RAM was 64MB, and the meager 64MB of storage could be expanded with SD cards. The compact 3.5-inch display sported a 320×240 resolution, which was standard for the time. Other peculiarities included a micro USB port and an EXT port, allowing users to connect the GP2X to a TV with a special cable and play their favorite retro games on a large screen. Talk about versatility.

This emulation beast was running an open-source Linux OS, meaning that, despite looking like other handheld consoles of the time, it was an actual handheld computer that you could use to watch movies, listen to music, read PDF files, and, of course, play games. While the number of the official game offerings was slender, to put it mildly, the community that gathered around it loved the device, resulting in an abundance of software for the GP2X, many of which were emulators.

The tiny machine was capable of running anything from the olden days, such as AtariST and Amiga, up to the original PlayStation – though performance wasn’t great – and GameBoy Advance. Overall, its emulation prowess was and still is legendary. The GP2X influenced basically all retro handhelds we have today. The device also inspired the arrival of the first handheld gaming computer. Together, these two accomplishments make for a pretty impressive legacy.

Baby Steps, Teething Issues, and Broken Promises

Three prominent members of the GP2X and Wiz emulation community, Craig Rothwell (CraigIX), Fatih Kilic, and Michael Mrozek (EvilDragon) loved the tiny emulation powerhouses, but were frustrated with the plethora of issues and shortcomings that were part of the GP32 and GP2X experience.

Rothwell and Mrozek were distributors for the South Korean handhelds in the UK and Germany, but the trio decided to take matters in their own hands. That’s how the OpenPandora project started.

In the words of Craig Rothwell… “we liked the GP2X and the GP32, but they had their faults: poor controls, strange internal design decisions, and the manufacturers not really understanding what people would want to use them for. As a distributor, it was frustrating. The culture barrier was hard to get past; what seemed like sensible and needed design decisions here in the UK seemed crazy to people in Korea. We reached a deadlock. There was no question about it: if we wanted a fantastic and unique open-source machine, we would have to go it alone. Thus, the crazy adventure started.”

And what an adventure it was. The first mention of the handheld dates back to 2007 on the now long-defunct GP32X forum, a gathering place for the GP2X community, where the trio asked the forum members what they would like to see in the handheld if it ever became a reality.

The feedback was heard, plans were made, and the result was the Pandora, the first proper handheld gaming PC. The device was based on an Arm CPU – no x86 here, unfortunately – and an Ångström-Linux-based open-source OS.

The project faced numerous setbacks, including an unsuccessful partnership with a China-based PCB designer, missed deadlines and major redesigns, unfulfilled orders despite buyers paying for their Pandoras in advance, and multiple price increases. In the end, OpenPandora managed to ship thousands of Pandora handhelds to customers, with the first batch shipped in 2010. Unfortunately, OpenPandora Ltd. owned by Rothwell, folded in 2013, leaving many pre-orders unfulfilled.

The German branch, OpenPandora GmbH, owned by Mrozek, continued to manufacture and sell the handheld for a couple more years. In 2014, Mrozek laid out plans for a spiritual successor to the Pandora, called the DragonBox Pyra. Similar to the Pandora, the DragonBox Pyra faced multiple setbacks, and by the time it launched in 2020, it was severely underpowered compared to handheld gaming machines made by GPD.

The Pandora was the first proper handheld gaming PC, but it wasn’t the only handheld gaming PC project that saw the light of day in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

Razer, of all companies, unveiled plans for a clamshell handheld PC in 2011, dubbed the Razer Switchblade. The device was to be based on an Intel Atom processor and Windows 7, and if it had come out, it would have been the first x86-based handheld gaming PC. Unfortunately, the project never made it past the concept stage, with some of the tech finding its way into Razer’s first generation of Blade gaming laptops. Razer pivoted instead towards a more conventional tablet-like device called the Razer Edge Pro, which debuted in 2013.

The Edge Pro was technically a gaming tablet powered by a beefy Core i7 CPU and a relatively powerful Nvidia GeForce GT 640M LE GPU with 2GB of VRAM, which was impressive to see in such a compact package. The device ran a full version of Windows 8 and was part of yet another of Microsoft’s pushes for Windows tablet PCs. Once you connected the GamePad controller add-on, you had a full-fledged handheld gaming PC that could run AAA titles of the time at playable frame rates. However, the price and the weight of 4.2 pounds made it a no-go for gamers dreaming of playing the latest and greatest games while lying on their sofas.

This era of early prototypes and wild designs ended in 2014 with a device originally called the SteamBoy, a handheld Steam machine based on the then-novel SteamOS. The handheld was among the first to feature a now-common setup shared between many handheld gaming PCs: a slate-like form factor with a screen at its center, dual analog sticks – or touchpads in the case of the SteamBoy – a D-pad, face buttons surrounding the display, and shoulder buttons at the top.

The SteamBoy later changed its name to Smach Z, and while it did manage to garner notable interest from fans and tech outlets alike, the project ended as vaporware, with the company behind it going bankrupt.

And while this period ended with a dismal outlook on the future of handheld gaming consoles, just a year later, a relatively small company residing in China would launch a device that would rekindle the handheld fire and that will, along with the Nintendo Switch, herald the golden era of handheld gaming consoles and PCs.

Notable devices of this era:

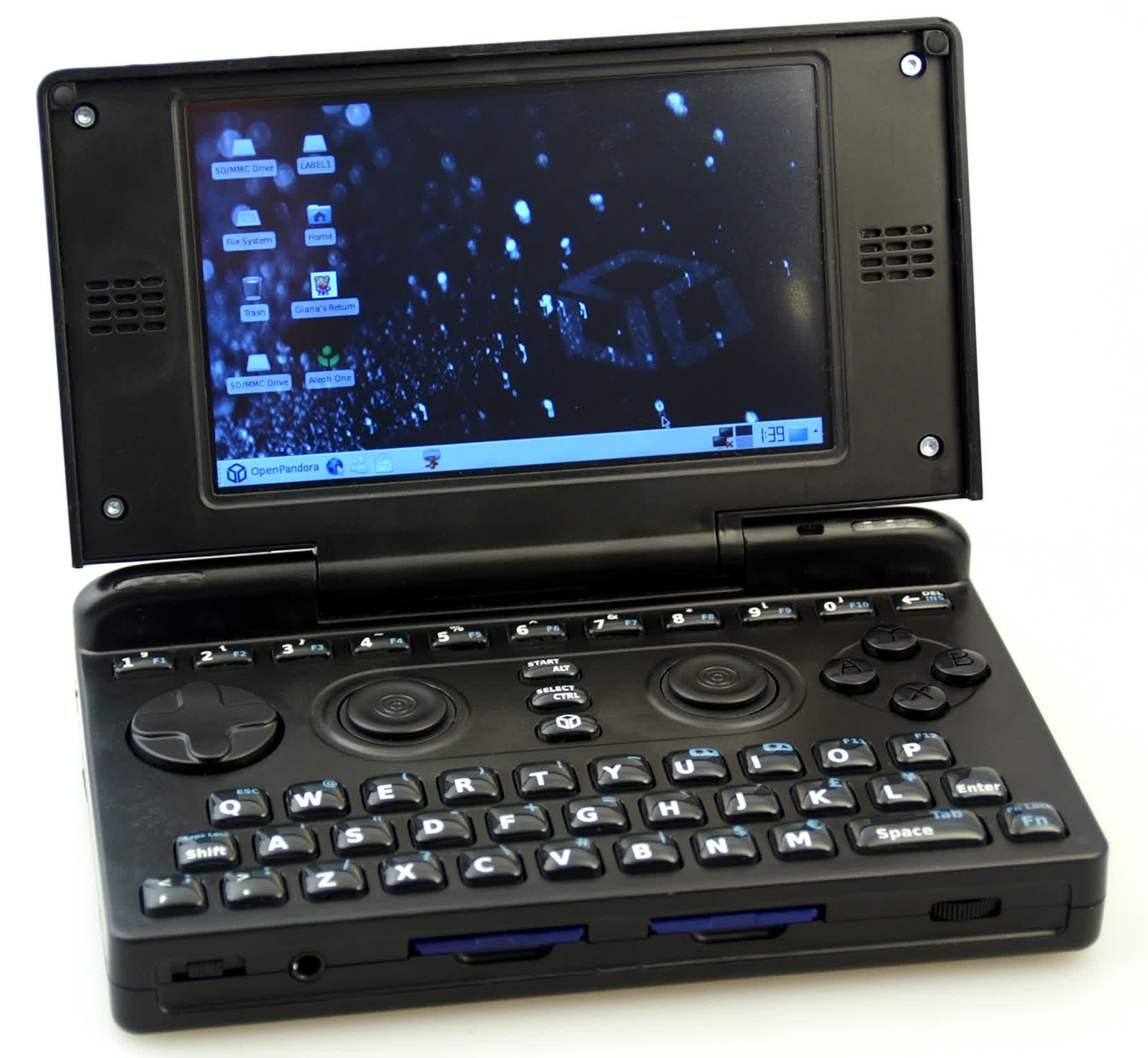

Pandora

A crowdsourced product before crowdfunding platforms were a thing, the Pandora achieved the impossible. The sheer fact that it launched at all and ended up in the hands of thousands of backers is an achievement in itself. While not based on an x86 CPU – x86 platforms were far from mobile-friendly back in 2007 – and while it didn’t support Windows, it was a full-fledged handheld PC running an open-source Linux-based OS, capable of anything regular laptop and desktop PCs of the time were capable of.

The first version of the Pandora packed a Texas Instruments OMAP3530 – an ARM Cortex A8 design running at 600MHz – coupled with a PowerVR SGX530 GPU, which allowed it to emulate consoles up to PSX, run Linux games, and play older PC games such as Baldur’s Gate, which were ported to run on Linux. With a price of about $350, it was a well-balanced mini PC with by far the best control scheme for gaming at the time.

The initial model only had 256MB of DDR-333 RAM, but the second iteration increased the amount of memory to 512MB. Other specs included a sharp 4.3-inch 800×480 LTPS LCD, Wi-Fi and Bluetooth, a full physical keyboard, and an assortment of ports, including two USB ports. While not considered a handheld PC at the time of its arrival, the Pandora is now regarded as the first dedicated handheld gaming PC.

Razer Switchblade

While it never moved past the concept stage, the Razer Switchblade was the main star at the CES 2011 showfloor, winning the CES 2011 People’s Voice award. When you look at it and the plans Razer had for the device, you can see why. Imagined as a handheld PC capable of running modern PC games, the Switchblade was to be equipped with a full-fledged Windows 7 and powered by an undisclosed Intel Atom processor.

The star of the show was the dual screens, with the bottom OLED display covered with transparent keys, acting as a keyboard with each key transforming depending on the game you were playing. This proved to be a great replacement for the usual controller setup, but the Switchblade was too ahead of its time to become a reality.

The x86 hardware, especially the iGPU portion of the equation, didn’t pack enough punch to allow for a competent gaming device in such a small footprint. Still, the device remained in the minds of gaming and hardware enthusiasts thanks to its unique design and its early hint of what an x86-based portable PC gaming console could look like in the future.

GPD Kindled the Torch — Valve Took It and Lit the Bonfire

Image source: u/arxym

GPD, also known as GamePad Digital, is a Chinese hardware manufacturer that cut their teeth designing cheap emulation handhelds such as the GPD 5005 and 7018, as well as sophisticated gaming handhelds running Android such as the GPD G5A.

Their pinnacle Android design, the GPD XD, saw reasonable success in the West thanks to its powerful internals, well-made controls, and great emulation performance.

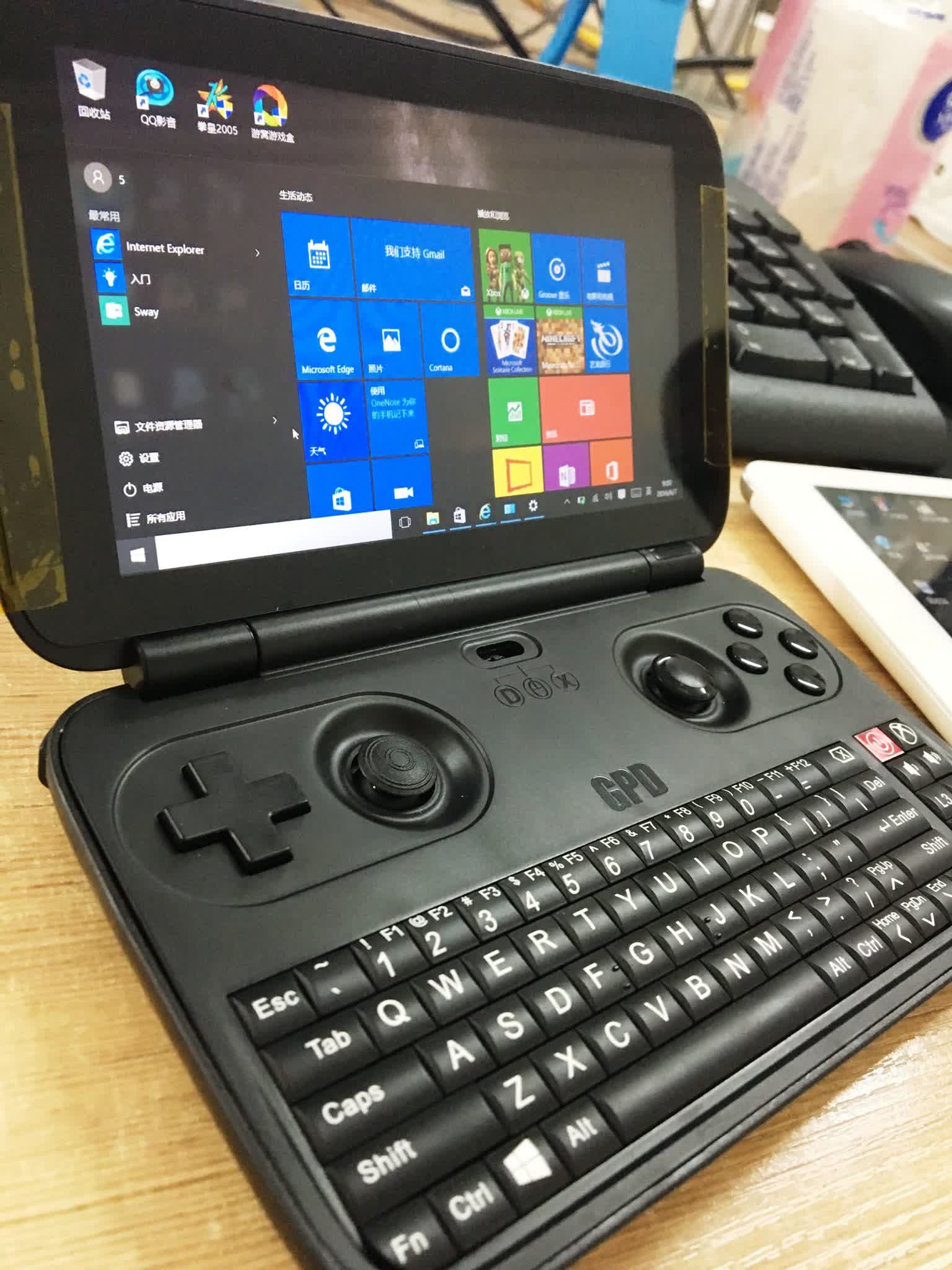

After honing its craft by creating Android handhelds, GPD’s appetite grew, and it was time for something bigger. GPD shared some rough mockups of their upcoming Windows handheld on the Dingoonity boards in late 2015, a place for China-made gaming handheld enthusiasts that was quite active back in the day. The discussion soon switched to high gear, and some 50+ pages later, we got a near-final design that was soon taken to IndieGoGo under the name GPD Win.

The GPD Win was a budget-conscious handheld gaming PC running Windows. It didn’t have much horsepower due to its meek Intel Atom CPU, but it was popular enough to warrant a successor, the GPD Win 2, which debuted in 2018.

The next generation of the handheld made the GPD name synonymous with handheld gaming PCs, with the Win 2 managing to catch the attention of mainstream tech media. While still underpowered in terms of gaming performance, the device was able to run older AAA titles such as TES: Skyrim, GTA V, and Batman: Arkham Asylum at playable frame rates, making it the first handheld gaming PC capable of providing a decent AAA gaming experience.

The GPD Win 2 came out less than a year after the Nintendo Switch, and thanks to the Switch and Alienware’s UFO handheld PC concept that took the world by storm and was the darling of the 2020 edition of CES, the mainstream gaming community revived its interest in handheld gaming. After years of pessimistic forecasts, which portended a quick death of dedicated handheld gaming devices thanks to the rise of mobile gaming, this was a breath of fresh air.

GPD continued to work on new handheld gaming PCs with the Win 3, which bore a striking resemblance to the legendary Sony Vaio UX series of UMPCs, launching in early 2021. By 2021, other Chinese brands, such as Ayaneo and One-Netbook, launched their own handhelds, and the nascent handheld gaming PC market slowly started to take shape.

Just months after the launch of the GPD Win 3, Valve announced the Steam Deck. Alienware had showcased its UFO gaming handheld prototype at CES 2020, but the UFO never moved past the concept stage, making Valve the first company outside China to offer a handheld gaming PC.

Instead of using off-the-shelf components, the Steam Deck incorporated a semi-custom APU made by AMD. Software-wise, the device was based on SteamOS, the long-forgotten operating system behind Valve’s failed Steam Machine initiative. The Steam machine dream somehow survived, but the new iteration was portable.

Steam Deck launched with varying success at the tail end of February 2022. Reviewers mostly praised the hardware and reprimanded the software, which felt quite unfinished during the early months of availability. But Valve persevered, with each software update improving stability, adding new features, enhancing gaming performance, and making more and more games playable.

Seven months after its launch, the library of playable games expanded to more than 5,000. Developers at Valve squashed most of the issues before the handheld celebrated its first birthday. Less than a year later, the number of Steam Deck-compatible titles surpassed 10,000. Handheld gaming PCs had reached a critical point, and big-name brands in the PC hardware space would soon follow in Valve’s footsteps.

Notable Devices:

GPD Win

Compared to modern handheld PCs, the 2016 GPD Win was a tiny machine, weighing only 300 grams and featuring a 5.5-inch 720p screen. At its heart was a humble Intel Atom x7-Z8700, sporting four cores with a 2.4GHz boost clock and an Intel HD Graphics 405 iGPU. Other notable specs included a diminutive 8.95Wh battery, 64GB of eMMC storage, and 4GB of LPDDR3 RAM.

The device also included a full QWERTY keyboard, a set of controls with dual thumbsticks, and a collection of extra keys right above the keyboard. For the time, its gaming performance was impressive, especially considering the device’s dimensions, its underpowered internals, and the $330 price point. While far from being capable of running current AAA titles of the period, the Win could churn out more than 30fps in older titles such as 2013 Tomb Raider, Skyrim, and Portal.

GPD Win 2

The Win 2 was a major improvement over the original. Launched in 2018, it packed double the gaming performance compared to the Win, thanks to the much more powerful Intel Core M3-7Y30 CPU paired with the Intel HD 615 iGPU and 8GB of LPDDR3.

Other notable improvements included a much chunkier 37Wh battery, improved build quality, and a 128GB SSD that was easily upgraded thanks to a screwed-in plastic cover located at the bottom of the device. It’s unfortunate how this hasn’t become a staple feature in handheld gaming PCs.

The device also featured a 6-inch display that retained the 720p resolution. As for the price, the $649 price point for early backers was much closer to the average pricing of modern handheld PCs, with the regular retail price rising to $900.

While the GPD Win was a sort of experimental prototype handheld gaming machine, the GPD Win 2 was a matured design potent enough to provide a decent gaming experience in recent AAA games. It still couldn’t run 2018’s or 2017’s heavy hitters, but it was getting pretty close.

Aya Neo 2021

The first handheld PC from AYA – now known as Ayaneo – launched in 2021 with an early bird price of $700 and a retail price of $869 for the 256GB version, in line with other handhelds of the time. Specs included the AMD Ryzen 5 4500U featuring the RX Vega 6 graphics, 16GB of LPDDR4X, a 7-inch, 60Hz, 800p screen, and a 47Wh battery.

The performance you got for the price was a tad behind the GPD Win 3, which launched close to the AYA Neo 2021, but the dream of getting playable frame rates in current AAA titles finally came true. The AYA Neo and GPD Win 3 could run titles such as Forza Horizon 4, Doom Eternal, and Jedi: Fallen Order at 720p at 30fps or higher, heralding a new era for handheld gaming PCs.

They had stopped being devices for emulation, playing older AAA titles, and indies, and evolved into capable devices that could tackle (almost) anything you threw at them. Sure, the AYA Neo couldn’t run Cyberpunk 2077 at serviceable frame rates, but we would get there sooner than we thought.

Valve Steam Deck

The Steam Deck brought a breath of fresh air to a market dominated by rather expensive devices from boutique brands. Starting at just $400 and capable of running almost every single game you throw at it at playable frame rates, the handheld has shown that yes, we can have our cake and eat it too, as long as we’re okay with forgoing Windows in favor of the Linux-based SteamOS.

The revival of Steam Machines, but in handheld form, features a semi-custom Zen 2-based APU with four CPU cores running at up to 3.5GHz backed up by an 8-CU RDNA 2 iGPU, with a total TDP of 15W. The biggest point of differentiation compared to other handheld PCs of the era, aside from the price, was 16GB of fast LPDDR5 memory that, along with the beefy iGPU, made the Steam Deck a surprisingly capable handheld that is still more than usable today.

Sure, it’s getting too meek for some 2024 heavy hitters, but the sheer fact that the device was capable of running AAA games that came after it at playable frame rates is worthy of praise alone. The 2023 OLED upgrade didn’t touch gaming performance, but the inclusion of a massively better OLED screen with HDR support and 90Hz refresh rate, along with a plethora of smaller upgrades, allowed the Steam Deck to live on for a couple more years until we get the imminent successor.

The Present: A Ton of Choices and a market with a bright future

Asus was the first big-name PC hardware brand to jump on the handheld gaming PC bandwagon with its ROG Ally handheld. A 2023 April Fool’s “joke” from Asus piqued the interest of many PC gamers who wanted an alternative to the Steam Deck and handhelds from boutique Chinese brands.

Less than three months after the “fake” announcement, we got the second handheld PC gaming device backed by a major company. The ROG Ally garnered notable success, and it looks like the company has plans for a successor.

Lenovo was the second major PC hardware brand to join the fray with the Legion Go, which iterated on the safe design of the ROG Ally and showed the audience that handheld gaming PCs have just started to evolve.

MSI, the third major player in the handheld gaming PC ring, took a safe path design-wise, but the company’s decision to forgo AMD hardware in favor of an Intel APU proved risky concerning the performance. That said, if nothing else, the MSI Claw marked the return of Intel to the handheld gaming PC arena, and we hope we will see more devices sporting Intel hardware in the future since competition is always welcome.

Another boon for handheld gaming PCs is the fact that the popularity of the Steam Deck brought the attention of many game developers, mostly from the indie space, many of whom are showing active effort to optimize their games for the relatively humble GPUs found in handheld gaming devices.

The rumblings in the handheld PC space made Sony return to handhelds, if only with a streaming device in the form of the PS Portal, which is a tad disappointing but still a welcome development. On the other hand, Microsoft is aware that the biggest downside of Windows-based handhelds is the OS itself, and the company might come up with a handheld-friendly, gaming-centric version of its operating system in the future. Microsoft’s Xbox arm is exploring the handheld space; we could get an Xbox handheld in the future. Whether it will be in a streaming device form similar to the PS Portal or one capable of running games natively remains to be seen.

Aside from overcoming issues tied to Windows, handheld PC manufacturers have two additional obstacles to overcome. The first is bringing the prices down to give their devices a fair chance of competing with the current dominating force in the space, the Steam Deck. Asus had a go with the Z1 version of the ROG Ally, but the insistence on the same 1080p display combined with the graphically anemic Z1 APU wasn’t the right move.

The second obstacle is an even taller order: convincing Intel, AMD, and maybe Nvidia – although unlikely considering the company’s AI-first strategy – to develop chipsets geared more towards gaming handhelds instead of settling for off-the-shelf parts that are grossly unbalanced in favor of the CPU and come with tiny caches compared to the needs of the CPU and GPU.

To make matters worse, Microsoft’s recent mammoth push into AI has led AMD to focus on increasing die space taken by NPUs in the company’s future chips, which could hurt the gaming performance of future APUs. Perhaps a semi-custom route is a good idea here, similar to what Valve pulled off when creating the Steam Deck.

Still, even with these setbacks, the handheld gaming PC market looks healthy at this point in time. We’re most likely in for at least another generation of the Steam Deck, ROG Ally, and MSI Claw, and you can bet that companies such as GPD and Ayaneo will continue to deliver handhelds with new, exciting designs like the Ayaneo Flip DS.

Despite AMD’s and Intel’s focus on NPUs and AI performance, the gaming performance of future PC handhelds will increase, if only at a slower pace, at least until on-package RAM becomes a standard feature.

Finally, the imminent arrival of the successor to the Nintendo Switch and the explosion of the handheld-friendly indie gaming market means that gaming handhelds, including PCs, will stay in the minds of the mainstream gaming sphere, guaranteeing press coverage and steering more and more gamers towards the handheld gaming avenue.

Notable Devices:

Asus ROG Ally

The first big device to follow in Steam Deck’s footsteps. The ROG Ally was also the first handheld gaming PC to feature VRR and AMD’s Z1 Extreme chip.

Aside from the SD card reader debacle and poor battery life, the hardware was top-notch, with the software being the point of contention. If the software woes included only the initial frustration during the setup process, when you curse at the clouds every other minute for the lack of a trackpad, things wouldn’t be that bad. But the fact that multiple Windows updates broke something – usually messing with performance in one way or another – and that the compact version of the Xbox app is more frustrating to navigate around than the regular UI proves that Windows is still not there yet when it comes to handheld PCs.

All in all, the ROG Ally is a pretty solid overall package, but we hope that future iterations will address the Windows experience, laughably poor battery life, and the lack of a trackpad.

MSI Claw

The MSI Claw marks Intel’s return to the handheld PC space. After its CPUs were exclusively used in early x86 models made by GPD, the arrival of Ayaneo heralded AMD’s domination for a couple of years. While, on paper, the Core Ultra 7 155H featured in the Claw is a mobile powerhouse, driver issues and less-than-great power efficiency put it behind AMD’s offerings.

Then there’s the usual Windows experience, which hamstrings every Windows handheld gaming machine out there. For what it’s worth, the rest of the hardware is on par with the ROG Ally and Steam Deck, and if the driver issues are sorted, the Claw could one day become a worthy competitor to the Steam Deck and ROG Ally.

Ayaneo Flip DS

While not very exciting when it comes to the APU powering it – we’ve got the Ryzen 7 8840U, which boasts the same gaming prowess as the 7740U but with the improved XDNA AI engine – the Ayaneo Flip DS is interesting for its dual-screen design, showing just how exciting a nascent product category can be when it’s in the phase of iteration and experimentation.

We hope to see more unique handheld designs before manufacturers come up with a set of “must-haves.”

—

The handheld gaming PC market is still in its infancy, but the evidence indicates that we’re in for an exciting ride. The history of handheld gaming PCs has many chapters left to be written.

[ad_2]

Source link