[ad_1]

At the same time, it was clear Modi would ease certain restrictions to revive a battered economy. He did just that as he extended the lockdown to May 3, while pursuing a strategy of gradual easing of restrictions in relatively unaffected areas. From April 20, ecommerce operations, industries in rural areas, manufacturing in special economic zones and transport of goods, among others, will be allowed. These relaxations differ according to how a district is classified — a hotspot or one with a few confirmed Covid-19 cases, or with no infections.

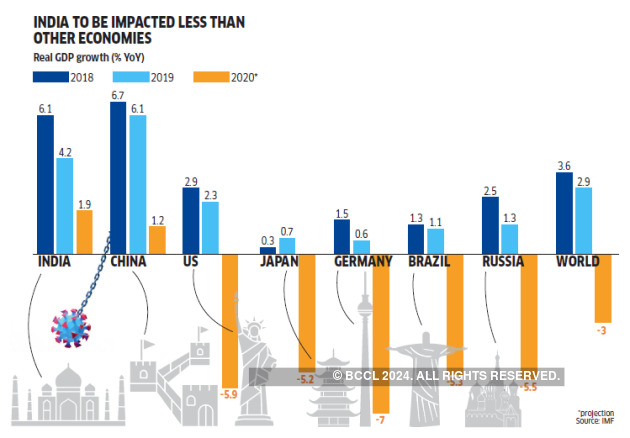

After May 3, more concessions are likely to be made in those parts of the country that are not seen to be vulnerable to Covid-19. But India, which has nearly 14,800 confirmed cases, including 488 deaths, will have to delicately balance the medical and economic imperatives to avoid ending up with a bigger problem on its hands after a few weeks.

There are no established playbooks globally on how to emerge out of a lockdown, according to Rajib Dasgupta, professor of epidemiology at Jawaharlal Nehru University. “Countries have different economic imperatives.” The lockdown has been eased primarily to provide a way for millions of poor workers to earn a living once again, and to give a gentle push to the sputtering economic engine. But the top priority is still containing the spread of the disease. A recent note by investment bank JP Morgan says social distancing rules should not be loosened until at least two weeks after evidence of the infection rate having peaked.

Different states, different strokes

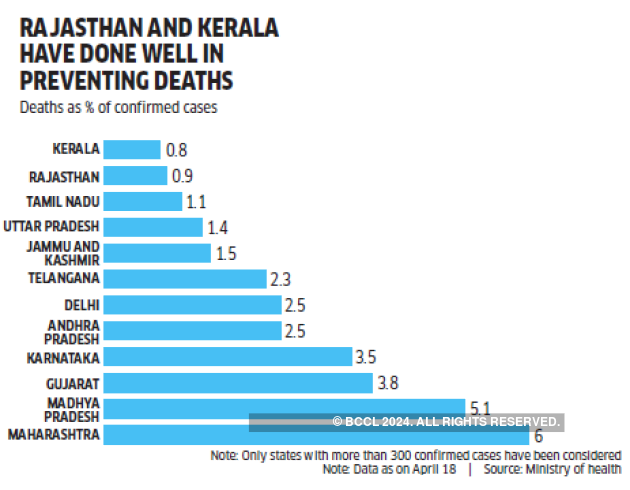

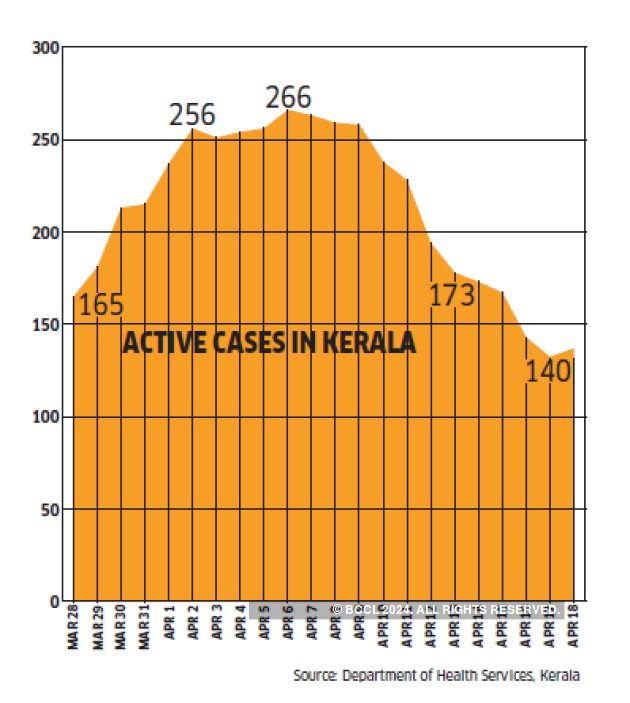

States like Kerala, where active cases are on the decline, and Karnataka, once among the three worst affected but now not even in the top 10, are better placed to explore ways to make life easy for their people after the lockdown than the likes of Maharashtra and Delhi, for both of which containment is still the top priority. “The story is not about states now, it’s about districts,” says Sangita Reddy, joint managing director of Apollo Hospitals Enterprise, India’s largest hospital chain.

The Centre on April 15 identified 170 hotspot districts and 207 potential hotspots, out of a total 734 districts. States are at different stages of transmission, and even within a single state, there could be large variations between its districts. For instance, Mumbai is the country’s worst hit district, but there are six districts in Maharashtra that haven’t reported a single case, while seven have just one case each, according to the state government. “No reported case doesn’t mean no case at all. We have to test 1-2% of population of an area before opening it up,” says Reddy.

Mathew George, professor of public health at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences in Mumbai, concurs. “Epidemiologically, we need population-level data, which is missing. We can do antibody tests to make an informed decision.” Antibody testing helps in figuring out how widely Covid-19 has spread by identifying those who have had an infection in the past and are now immune.

Also important is figuring out the demographic composition of a particular district, taluk or village and the diseases prevalent there. Given that the elderly are more at risk of developing complications from Covid-19, administrative units with a relatively high proportion of those above 65 years need to be treated differently from others. So do areas that have a high incidence of, say, tuberculosis.

“We should be using every shred of available data,” says Jishnu Das, an economist at Georgetown University who has researched India’s healthcare system. “We tend to see India as homogenous, but we need to break it into finer pieces, and we need data for that.”

Along with detailed statistics that will help authorities decide what sort of restrictions should be applicable to which parts of the state, once the lockdown is eased, the government should step up its surveillance to avoid further outbreaks or to act quickly if there is one. While containment zones are closely monitored, in a post-lockdown phase, entire cities or districts will need to be actively watched.

The government is hoping that its Arogya Setu mobile app will help in tracing those who came in contact with someone who tested positive later. But this will be effective only when a critical mass of people are using the app, which has been hobbled by privacy concerns.

One important factor in preventing a flare-up of infections is increased self-reporting by those with symptoms, believes D Prabhakaran, vice-president for research and policy at the Public Health Foundation of India. “We need to de-stigmatise the disease for that.”

When limitations on people’s movement are eased, local administrations should prepare their health infrastructure for a spike in cases.

The Union government has told districts to classify hospitals separately for mild, moderate and severe cases. As of April 11, India had 586 hospitals dedicated to Covid-19 treatment, with 1 lakh isolation beds and 11,500 intensive care unit beds, according to the Union health ministry.

The current protocol mandates hospitalisation of anyone who tests positive. This is likely to change if infections outnumber available hospital beds. Maharashtra, for instance, is already considering switching to a different protocol where mild cases remain quarantined at home. In the European Union, less than three in every 10 infected persons have had to be admitted to a hospital. “You put your health workers at risk when you hospitalise mild cases,” says Das.

Geography and demography

The other problem is the uneven geographical distribution of healthcare infrastructure. In Tamil Nadu and Kerala, there is one government hospital bed for every 900 people or so, but in Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, one government hospital bed on average serves nearly 3,000 and over 8,600 people respectively, according to the Union health ministry. So the large northern states are clearly less equipped to handle an outbreak after the lockdown ends than their counterparts in the south.

The other major challenge is handling the reverse migration of workers from cities once they are allowed to travel. If there isn’t enough work for them, they will be compelled to return to their villages. JM Financial Institutional Securities estimates that around 14 million migrants in India’s top 10 cities could go back home if there is no sign of economic revival. Nearly 2.5 million migrants are currently being provided food at 21,500 relief camps around the country. A large-scale movement of labourers to rural areas in poorer states in the north and the east could complicate matters for district authorities.

Even as India mulls the resumption of passenger trains and buses, it will soon have to take a call on allowing flights to operate again, but not before looking at the experience of countries like Singapore, Taiwan and Hong Kong.

Lauded for their quick response to Covid-19, these countries, along with China, started seeing a resurgence of infections, thanks to international fliers, including their own citizens returning home, around the middle of March. This forced these countries to tighten restrictions on the entry of foreigners. Singapore even went ahead and imposed a month-long lockdown in early April, something it had avoided till then.

Once international flights resume, George believes India should focus its resources on cities and states that see a lot of air traffic from other countries. “We need to have teams tracking international travellers. This has to be a long-term effort.” According to the JP Morgan note mentioned above, any government’s decision to restart international travel should depend not just on the spread of the disease within that country but on the global trajectory of Covid-19. “Border control relaxation should be delayed and be approached highly conservatively,” it says.

Countries around the world are preparing for a new normal in the foreseeable future where another large-scale Covid-19 outbreak is hardly a distant possibility, and India is no different. Central and state governments will have their work cut out for months not just in finding a way out of the lockdown but also in striking a balance between our health and economic priorities.

[ad_2]

Source link