[ad_1]

If you came here looking for a brief recap of Paul Weiland’s 2006 film, Sixty Six, then you are in luck. The story of a Jewish boy whose Shabbos spirit was dampened by his barmitzvah tragically falling on the same day as the World Cup final between England and West Germany in 1966 (spoiler alert: England win in controversial circumstances) was a niche topic that was met with mixed reviews, but it struck a resounding chord with me.

How I sympathised with poor Bernie Reubens’s plight as he stepped in front of the congregation at his synagogue, knowing that he was going to miss the biggest match of his short life and that nothing could make the disappointment go away, because 13-year-old me had been in his position. I understood. I felt his pain. I was Bernie, Bernie was me, I was in a film with a 63% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes, the film was about me. “Don’t worry!” I shouted at the television. “Maybe one day you’ll also get to write a needy, self-indulgent article in the Guardian about that time you missed a football match!”

And so, 15 difficult years on, here I am dealing with the trauma of my barmitzvah falling on the same weekend as a West Ham home game. And not just any game. A game against Egil Olsen’s struggling Wimbledon. The big one.

But the barmitzvah was the bigger one. I performed it to rave reviews on Saturday morning, receiving a 93% approval rating on Mitzvah Matters (“Has any boy ever hidden his reluctance about singing Ancient Hebrew text in public with such skill?” one critic wrote), accepted the acclaim of family, friends and strangers with great dignity and then turned my thoughts to West Ham’s match on the Sunday afternoon. Could my dad and I go to Upton Park for the 4pm kick-off and be back in time for my party in the evening? Would anyone notice if we were late? Would new loan signing Fredi Kanouté be up to much?

All questions that were treated with frankly admirable disdain by my footballistically-challenged mum, so I sat in my room, got ready and listened to the match on the radio (Sky Sports would not enter our house until 7 March 2001). Curses!

Then it happened. After eight minutes, Marc-Vivien Foé sprayed a pass out to Trevor Sinclair on the right wing. Sinclair took a touch, looked up and pinged a glorious crossfield ball from right to left, over Kenny Cunningham’s head, and towards Paolo Di Canio, who was preparing something; he was up to mischief, a flick had switched in his mind and something special was about to happen. Di Canio was in the air as the ball reached him.

“Sinclair’s cross,” Martin Tyler told those who did have Sky, the interest in his voice rising. “Over Cunningham’s head. Di CanioOOOOHHHHHIDONOTBELIEVETHAT! That is sensational! Even by his standards!”

Somehow defying the laws of physics, Di Canio had managed to maintain his balance and lace a searing right-footed volley past Neil Sullivan from the left of the area and into the far corner. It was a goal that required absurd levels of technique, athleticism and skill, just the way that he managed to control the ball when he was off the ground, and the West Ham supporters responded to what they had just seen not with the usual cheering, but with what sounds like startled, baffled laughter.

26,000 people shook their heads in disbelief in perfect unison and back at home, I shook mine in fury, silently fuming, honing my grudge-holding abilities. It had happened more than once that season; I never asked to be born.

On 11 September 1999, we missed Watford at home because it was Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. Di Canio scored the winner with a cheeky free-kick from a tight angle. On 18 December 1999, we missed a rollicking 4-2 defeat to Manchester United – Di Canio almost inspired a fightback from 3-0 down – because we had to go the birthday of a grown man who was wearing a novelty tie when he opened the door. This was less than ideal.

Another sore memory was school commitments ruling me out of the 1999/2000 League Cup quarter-final that had to be replayed against Aston Villa after West Ham fielded a cup-tied player, Manny Omoyinmi, in the first match. My dad went and I fell asleep listening to the radio, shortly after Frank Lampard had given West Ham the lead.

An hour or two later, my dad woke me up. “I’m back,” he said. “From the game.”

The game that I wasn’t at.

“Did we win?” I said hopefully. “Are we in the semi-finals?”

“No!” he chirped. “They were winning 1-0, but Villa won 3-1 after extra-time.”

Silence.

“Di Canio had a penalty when it was 2-1,” my dad continued, “but David James saved it. Anyway, you’d better go back to sleep, you’ve got school in the morning. Night!”

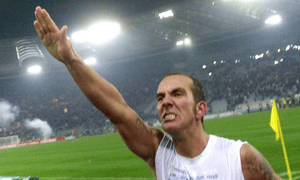

Villa were back at Upton Park for a league match three days later. It finished 1-1, Ian Taylor scoring for what felt like the 1,000th time against West Ham that week, Di Canio hooking in a late equaliser after a mistake by James. Di Canio then landed himself in hot water for making an obscene gesture after the final whistle, later saying that he had directed it towards an unnamed Villa player who had called him a “cheating Italian bastard”. It was never simple with him.

Although some of his actions since that time mean my feelings towards him are now mixed, Di Canio meant everything back then. A few months earlier, our class had been told to make a short speech in assembly about a hero of the 20th century. Most of the choices were obvious – Nelson Mandela, Winston Churchill, Jamie Theakston – but when it was my turn to speak, the entire school was treated to five minutes on the spectacular magic of Paolo Di Canio. There were some odd looks.

Hero worship can be problematic. It makes perfect sense when you are a kid, but it can make you look tragically childish as an adult. From a moral perspective, it is difficult not to agonise over whether it is acceptable to laud a man who expressed admiration for Benito Mussolini in his autobiography (the first chapter is called ‘Look at this beautiful, talented boy!’ and the book ends with Di Canio’s tiramisu recipe) and who has freely admitted that he is a fascist but not a racist. They say that you should never meet your heroes and even if you manage to do that, they are still liable to make a fascist salute after helping Lazio beat Roma in the Rome derby in 2005. Armed with that knowledge, it becomes easier, if a little gutwrenching, to remove the claret and blue glasses and view Di Canio in a different light.

Then again, Larry David saw nothing wrong with whistling Wagner, even though it led to an accusation that he was a self-loathing Jew. Some people find it more palatable to separate the art from the artist and maybe football is supposed to be an escape, the place where grown adults can spend 90 minutes acting like children again, and it would be disingenuous to deny that Di Canio was a hugely talented player.

He was captivating for West Ham in the 1999-2000 season and most weeks his team-mates were relegated to the roles of interested bystanders as Di Canio went about putting out various fires – and sometimes starting a few along the way. It is a team game, but he was capable of winning matches on his own, which is why he would take all the corners and free-kicks and why he would sometimes appear in the right-back position demanding the ball, ready to take on every last member of the opposition. He even took throw-ins.

His ego was huge, of course, and he was far from perfect. Di Canio played for Giovanni Trapattoni’s Juventus and Fabio Capello’s Milan, but his book is full of anecdotes about various bust-ups with managers, which probably explains why he never played for Italy. He fell out so badly with Capello during a pre-season tour of the Far East in 1996 that his last words to his manager were: “I’m not going to hang around here and look at your ugly penis face any longer!”

Di Canio was sold to Celtic, where he spent a season before joining Sheffield Wednesday. He struck up a partnership with another Italian forward, Benito Carbone, but his time at Hillsborough was brought to an abrupt end after his infamous push on Paul Alcock during Wednesday’s 1-0 win over Arsenal in September 1998.

Alcock’s tumble earned Di Canio an 11-match ban and pariah status in England. However that merely brought out the wheeler-dealer in Harry Redknapp, who could not resist bringing Di Canio to Upton Park for £1.5m in January 1999.

Redknapp and Di Canio hit it off immediately and West Ham qualified for the Intertoto Cup after finishing fifth, securing their place in the Uefa Cup by beating Metz 3-2 on aggregate in the final. Metz won the first leg 1-0 at Upton Park, but Di Canio was inspired in the return leg in France, creating goals for Sinclair and Lampard.

West Ham were set for a season of terrifying lows, dizzying highs and creamy middles, with Di Canio at the centre of everything that was good, bad or indifferent about them. When he played well, they could beat anyone and, much like Dennis Bergkamp in 1997-98, he could have run his own goal of the season competition.

He cemented his place in West Ham folklore when Arsenal visited east London in October 1999. Arsenal had thumped West Ham 4-0 at Upton Park earlier that year, but this time they were facing Di Canio on a mission. It was one-way traffic for long periods and Davor Suker and Bergkamp had already missed a couple of presentable chances for Arsène Wenger’s side when Di Canio collected the ball on the halfway line, from where he proceeded to dribble his way through the Arsenal midfield thanks to a series of ricochets, favourable bounces and limp challenges. The ball squirted to Sinclair, who appeared to control it with his arm before dinking it over David Seaman and into the middle, where Paulo Wanchope’s knockdown was turned in by Di Canio.

Arsenal laid siege to the West Ham goal in the second half, but Suker remained profligate and Bergkamp had a goal disallowed for a combination of handball and offside, before Wanchope flicked a long clearance from Shaka Hislop to Di Canio with 18 minutes left. It looked like Di Canio was heading down a dead end, but he turned past Martin Keown with his left foot and then cushioned a splendid shot high past Seaman with his right foot. “Out! Of! Nothing!” the BBC’s Barry Davies yelped and Keown was later seen wandering around Green Street with a confused look on his face, asking for directions back to the stadium.

West Ham held on for a 2-1 victory that owed everything to Di Canio and two months later he could be seen mounting a one-man offensive on Manchester United. The champions had stormed into a 3-0 lead inside the first 20 minutes, but Di Canio dragged West Ham back into it with two goals, delighting Davies again by rounding the goalkeeper for his second – by the 52nd minute. Nine minutes later, he looked certain to score his first West Ham hat-trick when he ran through on goal again, only to mess up an attempted chip that was easily saved by Raymond van der Gouw. United countered, Dwight Yorke made it 4-2 and when the camera panned to Di Canio, he was beating himself up.

Yet there were so many moments to cherish: a stunning equaliser in a 1-1 draw with Derby County, a solo effort in a 3-1 win over Leicester City, a bullet off the inside of the post in a 5-0 win over Coventry City. Every week, there was something that took the breath away and West Ham struggled when Di Canio was missing. He was out with a hamstring injury when Everton won 4-0 at Upton Park.

Controversy was never far away and Di Canio regularly clashed with referees, claiming that they treated him unfairly. He was booked for diving after a blatant trip in the area by Middlesbrough’s Gary Pallister and West Ham’s 2-0 defeat to Steaua Bucharest in the second round of the Uefa Cup was marred by Di Canio’s allegations that the referee, Claus Bo Larsen, had sworn at him. Di Canio was replaced by Joe Cole when West Ham were 1-0 down and it was later claimed that the referee had warned that he was going to send him off if Redknapp did not substitute him.

Di Canio boiled over during a game against Bradford City in February 2000. West Ham were trailing 4-2 to Paul Jewell’s strugglers and Di Canio’s indignation at seeing another obvious penalty appeal turned down by the referee, Neale Barry, led to him sitting down by the side of the pitch and telling Redknapp to take him off. Meanwhile Dean Saunders was busy hitting the post up the other end, wasting the chance to make it 5-2 to Bradford, and Redknapp told Di Canio to get on with it.

Eventually he roused himself and when Paul Kitson won a penalty for West Ham, Di Canio spied his chance to redeem himself after the miss against Villa. One problem, however – Lampard had grabbed the ball and had decided that he was taking it. He was wrong. After a long, heated and reasonably one-sided debate, Lampard backed off, Di Canio scored and West Ham fought back to win 5-4. Lampard, teed up by Di Canio, scored the winner.

The Wimbledon game came six weeks later and let’s let the man himself take us through his astonishing goal, writing in his autobiography:

“I got a lot of praise for the volley I scored against Wimbledon. Sure, it was a spectacular goal. What I did was extremely difficult, because it requires total body control, timing and balance. Compared to a bicycle kick or a scissors kick it is much more difficult, because in those situations your body weight is going backwards, which helps stabilise you. But when I struck the ball against Wimbledon, both feet were in the air, even just making contact was quite an achievement. But goals like that don’t just come out of thin air. I was able to do it because it was something I had practised for hours and hours in training. I attempted it so many times that it became an instinctive gesture. As the cross came in, I didn’t even think about what I was going to do. My brain just decided for me, it just happened.”

Di Canio was named West Ham’s player of the season and his goal against Wimbledon won goal of the season. Few efforts can top it for sheer chutzpah and imagination.

It was at least two months before I saw it but I have since managed to find a DVD of the entire match and, in the absence of having an actual life, recently spent an afternoon watching it. Di Canio was great.

Back on that March afternoon, my dad caught me on the stairs shortly after the final whistle. “Apparently Di Canio scored a good goal,” he said.

[ad_2]

Source link