[ad_1]

Image copyright

Flip Schulke

A stretch of the Berlin Wall, 1962. The wall was topped with barbed wire to prevent East Berliners from escaping

While most of the Berlin Wall anniversary coverage has focused on the day the wall came down, the seeds of revolution were planted in the 1960s, and fuelled by America’s civil rights movement, writes James Jeffrey.

When the Berlin Wall came down, thousands of people from around the world converged to celebrate the end of over 40 years of a divided Europe.

Among them was American photojournalist Flip Schulke, who had visited the wall many times since it was erected in 1961 in an attempt to document what he described as “man’s physical ability to build a bastion between himself and his own dignity, if he tries hard enough”.

As he mingled with the crowd, he heard on their lips not a German protest song, but the famous American civil rights anthem “We shall overcome”.

It was a song he knew well.

As a photojournalist in the 1950s and 1960s, Schulke captured many significant moments in the nation’s struggle for civil rights in the 1960s, such as the marches to end segregation from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, and Martin Luther King’s funeral in 1968.

Image copyright

Flip Schulke

After the Berlin Wall went up in 1961, Schulke brought his civil rights experiences with him as he attempted to capture the wall’s symbolic and physical power.

“This is the wall that fear built,” Schulke wrote in notes during his visit to the wall in 1962. “This was the wall where hate stood guard, and men stooped much lower than angels. On one side it was bright and clean from the sun of freedom. (On) the other dark and bitter – the rot of slavery.”

Comprised of bricks, mortar, steel wire and jagged glass fragments to deter climbers, the wall both appalled and shocked Schulke, who described it as having a “jerry built” look.

“It just can’t be real,” he noted, adding that the wall was a “monument to human misery” that “splits the world in half like a melon”.

Image copyright

Flip Schulke

Woman walking alongside Berlin Wall, circa 1962-1968

He recalled how on the western side German children played tag in the shadows of tank traps while on the other side children stood “dull-eyed and pinch faced in darkened doorways – wondering how one learns to laugh”.

As East German guards looked at him through their binoculars, Schulke observed recent East German escapees in West Berlin standing near the wall and signalling to friends and relatives back in East Berlin or waiting for relatives to appear.

“One woman waited five hours to see her mother who never turned up,” Schulke wrote. “Another couple stood by the River Spree, the girl crying softly, trying to catch a glimpse of her mother across the river.”

During Schulke’s early coverage of the civil rights movement, he had a relatively balanced journalistic outlook and tried to see both sides, says Gary Truman, a long-time friend and former colleague.

“But that faded quickly because he said that sometimes there is no other reasonable opposite view, there was only right and wrong,” Truman says.

“I think his coverage of the Berlin Wall stated immediately: this simply is wrong.”

Image copyright

Flip Schulke

During the civil rights marches from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, protestors referred to themselves as the “Selma Wall”

Schulke saw both the wall and the civil rights movement as part of “a greater conflict over universal human freedoms,” says Truman, who became the archivist of Schulke’s photo collection after the photographer’s death in 2008.

“Similarities always exist in the artist’s eyes.”

Schulke was far from alone in seeing the parallels between division in America and in Berlin. Even before the famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech by President John F Kennedy, his brother Robert Kennedy came to Berlin as US Attorney General in February 1962.

“For a hundred years, despite out protestations of equality, we had, as you know, a wall of our own – a wall of segregation erected against Negroes,” Kennedy said. “That wall is coming down.”

Image copyright

Flip Schulke

German soldiers at the Wall, circa 1960s

“For generations, critically engaged Americans visited Berlin to see the wall, and think of the wall, as a metaphor to think about division in the US,” says historian Paul Farber and author of the forthcoming book A Wall of Our Own: An American History of the Berlin Wall.

In the 1960s, it became a symbol for American segregation. In the 1980s, for nuclear disarmament.

“Within days of the Wall going up, it was being used to talk about the colour line in the US,” Farber says.

That process of shifting representation continues to this day for Americans.

“The US prison system, unfair housing practises, all these physical and social walls can be understood when drawing historical and current connections to Berlin,” Farber says.

“The idea of a border wall haunts us today.”

Schulke was born in 1930 and grew up in New Ulm, Minnesota, a town with a significant German American population, a fact that Truman says must have driven some of Schulke’s interest in Berlin.

His got his nickname “Flip” due to an early interest in gymnastics. Schulke also spent part of his childhood in the South, where he felt conflicted watching the way his parents treated black servants, Truman says.

Image copyright

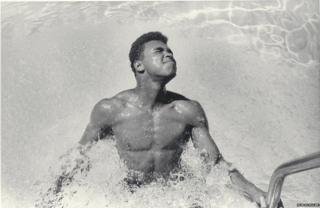

Flip Schulke

Muhammad Ali, 1961

After launching his freelance photography career, he worked for the likes of Life magazine and other US and European publications.

He covered the Cuban revolution of Fidel Castro as well as the triumphs and tragedies of American life, spanning space launches to hurricanes, as well as chronicling the leading entertainers and athletes of his time such as the boxer Muhammad Ali.

A collection of 300,000 of Schulke’s images are housed in the Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at the University of Texas at Austin.

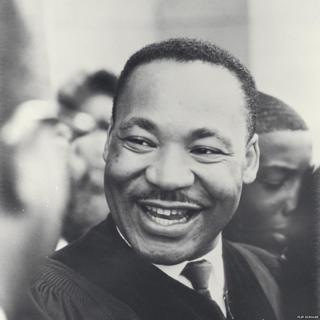

Schulke’s involvement in the civil rights movement began in 1956 and was influenced and often facilitated by his friendship with Martin Luther King, whom he met in 1958 when Schulke was on assignment for Ebony Magazine covering a rally in a Miami church.

Schulke wanted to ask King some questions. King, due to his busy schedule, asked Schulke to wait and to come to a post-rally gathering at a house belonging to a member of the congregation.

“They ended up talking most of the night,” Truman says.

Image copyright

Flip Schulke

Schulke’s personal collection of 11,000 photos of King and his family is the largest in the world

They stayed in touch over the years and Schulke was invited to King’s home for Sunday dinner several times while on other assignments in the Atlanta region.

“History, justice, fairness and emotion – just what feels right – all played a part in his photography,” Truman says.

Schulke wasn’t the only American photographer whose experiences with the paradox of American freedom and institutionalised racism influenced his work in Berlin.

In his book, Farber discusses photographer Leonard Freed, who visited Berlin in August 1961.

In one picture Freed took, a black soldier stands in the American sector of Berlin in front of the rudimentary wall going up.

“We meet silently and part silently,” Freed wrote of the encounter afterwards in his book Black in White America.

“Between us, impregnable and as deadly as the wall behind him, is another wall. It is there on the trolley tracks, it crawls along cobble stones, across the frontiers and oceans, reaching back into our lives and deep into our hearts: dividing us, wherever we meet. I am White and he is Black.”

When King was assassinated in 1968, Schulke stopped covering the civil rights movement and turned towards more commercial projects, pioneering underwater photography working alongside the likes of the maritime explorer Jacques Cousteau.

“It was just too painful to continue with the news coverage after the loss of King,” Truman says.

Image copyright

Flip Schulke

The one-man mini-subs of Jacques Yves Cousteau. In these photographs, the subs are diving in Lake Titicaca, 12,500 feet up in the Bolivian Andes, circa 1967-1975

But Schulke returned to the wall again and again throughout his life, often self-funding his trips because he couldn’t stir the interest of editors who didn’t see a story in something that they considered would always be there, Truman says.

During the 1970s he photographed the wall from the same vantage points that he had before, to illustrate the growth and reinforcement of the wall.

He saw how it was becoming “more of a void than a wall,” says Ben Wright, a researcher at UT Austin’s Briscoe Center for American History where Schulke’s archives are housed.

“The removal of trees and buildings had created a barren strip 200 yards wide that along with walls, traps and guards strangled the entire western sector of the city.”

Find out more about East Germany, 1989

Then in 1980, Schulke returned to document the replacement of the original wall with a new one made of concrete. While still imposing, he also noted how it had developed a strange aesthetic quality, due to its minimalist uniformity blanketed in murals and graffiti.

When Schulke returned in 1989, arriving a few weeks after the 9 November decision by the East German authorities to let East Germans cross for the first time in a generation, he found himself as shocked as he had been the very first time he had seen the wall, though for very different reasons.

What had once been “something sinister… a dark forbidding monstrosity was now a joke,” he wrote. He photographed East Germans shopping in West Berlin, border guards smiling and waving, children hawking pieces of the wall to tourists.

Image copyright

Flip Schulke

A German soldier walks near the Berlin Wall in East Germany, March 1990

Schulke visited the East German homes of the people he had been photographing across the Wall for decades, noting that in “every case I was welcomed in to photograph back toward the West, over the Wall, the view that I had wondered for so long – what would it look like?”

He recalled encountering East German activists who told him they had succeeded in bringing the wall down by repeating the non-violent protesting and marches of the civil rights movement.

“I remembered as I saw these people making their own free charge for democracy and freedom, Martin Luther King, Jr, saying: ‘Free at last, free at last’,” Schulke wrote.

.

[ad_2]

Source link