[ad_1]

Brodie, Colman and Widdowson may sound like a law firm, but these three names should be remembered for enduring innovations that changed football and stood the test of time.

Goal nets

There are few sights more aesthetically pleasing than watching a ball ripple against a goal net. The net adds an extra dimension to the art of goalscoring. A sensory bonus. Whether it is a sumptuous volley from outside the penalty area – think Andros Townsend’s screamer against Manchester City in 2018 – or a clinical finish from inside the six-yard box, the net embellishes the goal. Had it not been for the ingenuity and foresight of a Victorian engineer from Liverpool, we might not enjoy the pleasures of the rippling net.

The first set of rules published by the FA in 1863 stipulated that goalposts had to be eight yards apart – one of the original rules still in operation. The crossbar was introduced later, initially as tape in 1866, before solid bars were made mandatory in 1882. It is fitting that one of the most disputed goals in history was scored on the centenary of the crossbar’s introduction.

Goal nets came a few decades later thanks to John Alexander Brodie, an engineer from Liverpool who designed the UK’s first ring road, the Mersey Tunnel (the world’s longest underwater road tunnel at the time), and much of the architecture in New Delhi. In October 1889, Everton fan Brodie went to watch his team play Accrington Stanley at Anfield (Everton’s home ground at the time). Everton thought they had scored a winner but, with only goalposts and a crossbar to judge, nobody could be absolutely sure if the shot had passed through the posts, so they had to settle for a draw.

Brodie was so incensed that he tried to find a solution. As he walked away from the game, he put his hands into his trouser pockets and struck upon the idea of creating “a pocket in which the ball may lodge after passing through the goal.” Brodie got to work on a variety of net designs. One of his revolutionary ideas was to attach bells to the nets that would be triggered when the ball touched them, an early prototype of goalline technology.

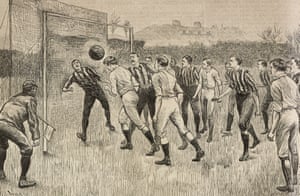

He was granted a patent the following year and the net passed a trial in a north v south representative match in Nottingham. It must have given Brodie a sense of satisfaction that the very first goal to hit the back of the net was scored by an Everton player, Fred Geary. The match was refereed by Sam Weller Widdowson, who invented shin pads – more of which later.

Within a year nets were included in the FA’s rules. They featured in the FA Cup final for the first time in 1891 and were made compulsory at the start of the following season. Of all his impressive engineering feats, the creation of goal nets was Brodie’s pride and joy.

Shin pads

Widdowson was an all-round sportsman and in his playing days caught the attention of William McGregor, the man who founded the Football League. “Widdowson was a great sportsman,” wrote McGregor in an article published in 1902. “He was the most dangerous centre in the whole of England. He was a magnificent dribbler and a splendid shot, and he could run like a hare. They always turn out the fastest hurdlers in Nottingham and Widdowson was one of the best of them. There was not a better known footballer in the country. His sensational dribbles – and they really were sensational – were always the features of his games.” It was said that Widdowson could run 100 yards in 10.25 seconds and a mile in four minutes, 50 seconds.

Like his contemporary Brodie, Widdowson created a piece of football equipment that has lasted until current times, but the difference was that Widdowson’s was an adaptation from another sport. Widdowson not only captained Nottingham Forest – and became their chairman while still playing – but he also represented Nottinghamshire at cricket. He took his inspiration for shin pads from the summer sport.

In 1874 Widdowson came up with the idea of footballers using smaller versions of cricket pads to lessen the impact of hacking. Shin pads were worn outside the socks and initially Widdowson was ridiculed for the strange sight of these new-fangled guards, but that derision soon dissipated. Even though most players have worn them for more than a century, Fifa did not make shin guards compulsory until 1990.

This was not Widdowson’s only innovation. He was also instrumental in experimenting with floodlights, using gas lamps for Forest-County derby matches. And, in his days as a referee, he was an early advocate of the whistle, which was brought in to replace the white flag that had been previously used to draw attention to the referee’s decisions.

Dugouts

Another name that should be added to the gallery of early football innovators is that of Donald Colman, although his original surname was Cunningham. His enthusiasm for playing football was not shared by his father, a deeply religious man who disapproved of a sport that he considered ungodly, so he adopted his grandmother’s maiden name.

Colman had a long and varied career. He started out as an amateur for Glasgow Perthshire before turning professional with Motherwell at the age of 27. Two years later he moved to Aberdeen, where he spent most of his career, was made captain and won four Scotland caps. He was still playing for his last club, Dumbarton, at the age of 47, but by then his attention had switched to coaching.

His coaching philosophy was way ahead of its time. Colman insisted on a possession-based game with players creating space by running off the ball, a style that could be considered a forerunner of tiki-taka. As a deep thinker about the game, Colman was keen to learn more about coaching beyond British shores so spent successive summers coaching Norwegian club, SK Brann of Bergen. And it was at Bergen where he came across his idea for the dugout.

While in Scandinavia Colman noticed that coaches relayed messages to players from open-fronted huts on the side of the pitch. He started toying with the idea of having a sunken sheltered area that afforded the best vantage point to study the players’ footwork at eye level.

As soon as Colman was appointed as coach at Aberdeen in 1931 he brought the idea of the dugout to Pittodrie – the very first to be installed at a professional football ground. The roof above his head allowed him to keep his copious notes dry from the elements.

Just before the second world war, Everton travelled to Pittodrie for a pre-season friendly and were so impressed with the dugout that they soon installed their own at Goodison Park. Dugouts quickly became common and their scope expanded to accommodate more coaches and substitutes. As the number of people using the dugout increased, they were moved above ground and, in 1993, they were enshrined in the laws of the game as Fifa established the technical area, clearly marking out the boundaries for each team.

Colman was a real football man – he also designed his own football boots – and his love of the game has passed down through his family. His great-granddaughter, Rachel Corsie, currently captains the Scotland women’s team. He had the last laugh over his father in the end.

Richard Foster’s new book Premier League Nuggets is out now and you can follow him on Twitter.

[ad_2]

Source link