[ad_1]

In context: Part of what led to Stadia Games and Entertainment division’s early demise is the underwhelming number of subscribers the platform managed to garner since November 2019. Although Google has not posted official numbers, Bloomberg quotes insiders stating Stadia missed controller sales and monthly active user count goals “by hundreds of thousands.” The low adoption rates may be attributed to how the platform was marketed and released. This is arguably the biggest waste of money and resources in Google’s history.

Stadia broke from Google’s typical “start small and build” philosophy of product development. Unlike other Google products with long beta cycles, like Gmail, it was marketed and hyped as a full service that was ready to kill off consoles. Stadia head Phil Harrison said it was “the future of gaming.” Speaking with anonymous sources, including former employees of the now-defunct development house, Bloomberg and Wired uncovered some details surrounding what was going on leading up to the closure.

Harrison is a veteran of console gaming, having served as an executive at both PlayStation and Xbox. While many in the Stadia team knew the platform was not ready to take on console gaming, Harrison was not dissuaded and “positioned Stadia as a traditional gaming platform full of bells and whistles.”

Take-Two CEO Strauss Zelnick said Google “overpromised” with Stadia. “The launch of Stadia has been slow,” Zelnick stated last June. “I think there was some overpromising on what the technology could deliver and some consumer disappointment as a result.”

Harrison’s console-like approach affected the overall Stadia business model. For instance, it required the $130 Founder’s Edition controller bundle to have some way to offer pre-orders. Console makers generally use pre-order sales to grease the cogs of assembly lines and get initial product shipments out the door. This was not necessary in Stadia’s case since just about any controller will work with the service, and Chromecast dongles were already well into their production cycle.

The subscription model also led many to believe early on that the service would operate much like Netflix with an all-you-can-play experience for one monthly fee. As it turned out, the subscription covered only a handful of games. At as much as $60 per title, Stadia’s other offerings were no cheaper than buying a title elsewhere. As a result, potential users did not see the point to pay on top of the subscription, especially when they already owned some of the same titles on consoles or PC.

However, lack of user interest was not the only thing troubling SG&E. Former and current Stadia employees speaking with Wired indicated that Google might have been ill-equipped in both leadership and resources to operate a game studio. “After pouring tens of millions of dollars into two game studios, Google couldn’t stomach the expensive and complicated creative process necessary to build high-caliber video games—especially considering Stadia’s unremarkable subscription numbers,” said the anonymous employees.

Google had already spent millions of dollars enticing third-party developers to release games on Stadia but knew it needed exclusive content to attract users to the platform. According to the insiders, this drive to create games for the sake of the system was the crux of the problem. The employees expressed that “Google wasn’t funding games to sell games; it was funding games to sell Stadia.”

To that end, it opened Stadia Games and Entertainment, hiring scores of workers and scooping up Typhoon Games along the way. Google lured veteran designers with the promise of a more relaxed work environment without the “crunch” and worry of layoffs. It also hired industry vet and founder of Ubisoft Toronto Jade Raymond to head up the division, so what could go wrong? Apparently, a lot.

For one, Google’s ambition was to release AAA Stadia exclusives, but didn’t have the existing talent for creating such content in time for launch.

“Google is really an engineering and technology business,” said one source fortunate enough to still be employed with Stadia. “Making content—it requires types of roles that don’t typically exist at Google.” So the company went on a hiring frenzy, but its selection process was cumbersome, taking up to nine months to approve a new hire. The sources say it was hoping to hire at least 2,000 employees within five years. This goal became achievable after streamlining its hiring process to one more structured to game designers rather than software engineers.

However, after joining the fold, developers encountered a work environment not conducive to producing games. For example, three of Wired’s sources confirmed that Google disallowed crucial game development tools because of “security” reasons. Another hurdle was Google’s insistence of putting Stadia features above gameplay features.

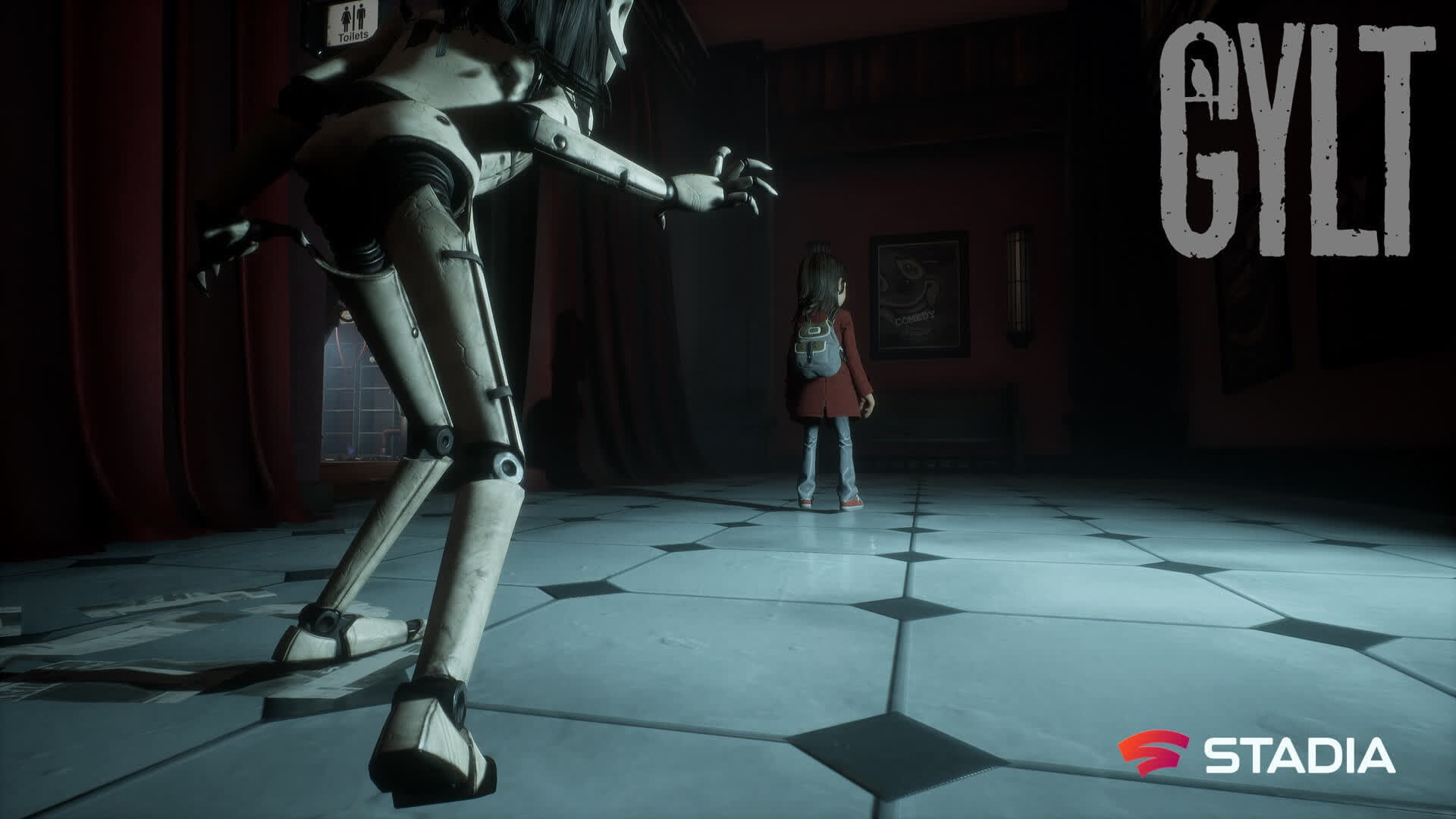

“For a long time, the mandate for games included requirements to espouse the Stadia-specific mentality, so, like, taking advantage of features meant specifically for Stadia,” said one of the insiders. Despite the desire to launch Stadia with first-party exclusives, being late to the game, throwing up development barriers, and having unrealistic expectations of development times, Google was forced to face the hard truth that it would not have anything new to offer when the platform debuted other than the indie title Gylt.

This shortfall did not seem to dampen Google’s commitment to developing exclusive in-house content. It continued hiring and had actually accumulated a decent stable of talent. However, the pandemic hit in early 2020, and by April, Stadia had announced a hiring freeze. As the pandemic stretched into 2021, the company became acutely aware of how AAA development costs could ramp up, and suddenly the prospect of in-house exclusives became much less attractive.

“I think it’s a lack of understanding of the process,” said an insider. “It seemed there were executive-level people not fully grasping how to navigate through a space that is highly creative [and] cross-disciplinary.” In other words, Google had bitten off more than it could chew. Despite upper management coming to this conclusion, they led developers to believe everything was still status quo as far as SG&E was concerned.

On January 27, Phil Harrison issued an email containing the “high-level platform budget and investment envelope” for 2021. In it, he also mentioned that SG&E “had made great progress building a diverse and talented team and establishing a strong line up of Stadia exclusive games” and noted that the division’s budget was forthcoming. However, he was apparently just blowing smoke.

Google has no intentions of abandoning the Stadia platform

Just days later, coinciding with the launch of SG&E’s only completed project, Journey to the Savage Planet, Google announced it was closing its studios. It promised employees with relevant skills would be placed elsewhere in the company, but most of the 150 game designers were laid off. Wired’s sources said that the studio’s closure was not that surprising considering the inner turmoil, but the fact that it came so close to Harrison’s praise of the division and the launch of its only game was somewhat shocking.

At this point, Google has no intentions of abandoning the Stadia platform. There are several competing services from the likes of Nvidia, Sony, Microsoft, and others who want on the ground floor of cloud gaming. So it would be premature to pull out this early— after all, Sony has been trying to perfect PlayStation Now for over six years. However, if what Stadia leakers say is true, Google might want to reassess how it markets and runs a service that still has yet to prove itself.

Image credit: Colleen Michaels, Daniel Constante

[ad_2]

Source link